In the 1990s, along with many other fundamental changes, Poland began a painstaking analysis of its education system. Experts quickly focused on two major problems: only 7 percent of the population was enrolled in higher education, and vocational schools were not teaching basic literacy.

In short, those gaps meant that Poland was not training a workforce that could move the country toward a new, more vibrant, economy. But today, 25 years later, Poland is a country with a dynamic workforce whose competencies in reading, mathematics and science exceed OECD and EU averages.

In the late 1990s, educators and lawmakers in Poland began making major changes. One big change means Polish students now spend more time in school: the country expanded mandatory schooling from 8 years to 9, adding another year in the primary grades.

Poland made other adjustments. The state began shedding central control of elementary school operations by transferring decision-making to newly reformed and empowered local governments. And the government began focusing on adult education and on critical thinking skills, instead of memorization, for younger students.

Another major reform reorganized secondary schools. Poland delayed the selection of students into general secondary or into technical schools by a year from the age of 15 to 16, offering a broader general education but still preparing students for the workforce by teaching them skills for specific careers. The pressure for change was clear; as Poland’s economy was evolving, so was its demand for workers.

“It was apparent that neither basic vocational school students nor their teachers believed that much could be achieved as far as general skills were concerned,” writes Professor Zbigniew Marciniak, one of the key architects of the Polish education reform of the late 1990s, in a report for the World Bank. “Emphasis was instead placed on basic professional skills. This contrasted sharply with the soft competences increasingly required by the labor market of the free economy. The public was becoming increasingly aware that general skills are of key importance when faced with the need to change job or even profession.”

And, to make sure the reforms were working as intended, Poland also introduced independent national assessments that not only analyze student progress but also compare individual schools with each other.

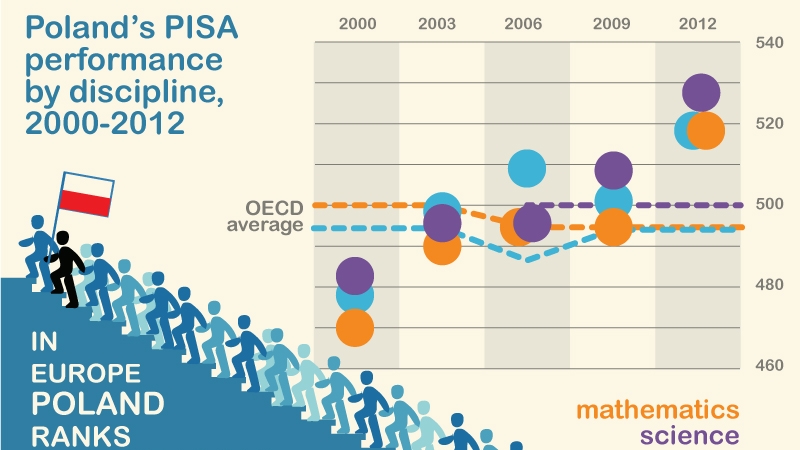

At about the same time Poland was reforming its education system, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the OECD, launched an international assessment of achievement and application of key knowledge and skills of 15 year-old students, the Program for international Student (PISA). In 2000, Poland’s PISA results were below the OECD’s averages. But 3 years later, Polish students’ results had improved, and on each PISA test since 2003, Poland’s scores have risen steadily. In the last assessment cycle, conducted in 2012, Polish students placed an impressive 2nd in reading scores and 6th in mathematics in Europe.