The United States, once a global leader in infrastructure competitiveness, now ranks 16th in the world.1 This decline shows no signs of abating as federal, state and local funds for infrastructure remain constrained, and government resources remain centered on health care, social security, and defense.2

Underinvesting in existing and new infrastructure reduces the productive capacity of the U.S. economy. The United States could eliminate this major drag on economic growth and protect against a $3.1 trillion loss in gross domestic product (GDP) through sizable infrastructure investments through 2020, according to a 2013 study by the American Society of Civil Engineers.3

In an era of limited federal funding for infrastructure, PPPs are an increasingly used tool for U.S. state and local governments to bridge resource gaps. This article explores key PPP trends and takeaways from the past decade in the United States and analyzes some of the factors that will determine industry growth going forward. The article also offers specific, tangible evidence of the benefits of PPPs in the United States that demonstrate that significant public value can be created through the responsible fusion of private and public sector resources.

Brownfield to greenfield: A short history

Since the catalyzing $1.8 billion Chicago Skyway lease was completed 10 years ago, the U.S. PPP market has developed dramatically. From 2005 to 2014, 48 infrastructure PPP transactions with an aggregate value of $61 billion reached the formal announcement phase. Of the forty-eight deals, 40 transactions — or more than 80 percent — successfully closed. 2012 was the busiest year on record for PPPs that reached financial close, with nine such transactions achieving completion during the year. A summary of historical transaction activity is included in Table 1.

Despite a sizable and growing track record, PPP skeptics in the U.S. often narrowly focus on the handful of announced transactions that did not close — most notably, Texas’s $3.5 billion SH-121 (2007), the $12.8 billion Pennsylvania Turnpike lease (2008), the $452 million Pittsburgh Parking concession (2010), and the $2.5 billion Chicago Midway Airport lease (2009, 2013).7

The most common thread in these unsuccessful PPP initiatives is a lack of political consensus to support the underlying project through to completion. If a jurisdiction is divided on partisan or other lines as to whether a PPP is the correct approach, it reduces both the chances of success and the appetite of bidders to present attractive proposals. Without a real consensus at the outset, history suggests that the risk of a PPP being thwarted or mischaracterized by opponents is high. This is true even at the local level in cities that enjoy “municipal home rule,” which generally provides broad legal authority and protection from interference at the state level.8

Political risk, however, was not the only defining characteristic in the early years of the US PPP industry. Financial market conditions also played a fundamental role.

In 2008 and 2009, the global financial crisis profoundly reshaped the US PPP market. Prior to the crisis, only 10 infrastructure PPP transactions had been announced, reflecting the industry’s nascent stage. The vast majority of PPPs from 2005 to 2007 were privatization-style transactions involving “brownfield,” or existing assets. In such transactions, the private sector assumed significant risks and underwrote aggressive assumptions regarding future levels of demand.

The largest completed PPP of the pre-financial crisis was the $3.8 billion lease of the 157-mile Indiana Toll Road, which is now undergoing a financial restructuring via Chapter 11 bankruptcy.9 At this point, such privatization transactions — which were highly politicized despite the private sector overpaying — appear to be a relic of the credit bubble and financial history.

Since the crisis, the U.S. infrastructure PPP market has almost entirely shifted away from “brownfield” transactions in favor of “greenfield,” i.e., new-build projects. In a greenfield context, the primary value of the PPP model comes not from monetizing an asset, but rather from delivering a needed project more effectively. Such projects are often tendered by governments as “availability-payment” transactions, which entitle a developer/private consortium to receive periodic payments as long as the asset is “available” to the public at the standards set forth in the contract.

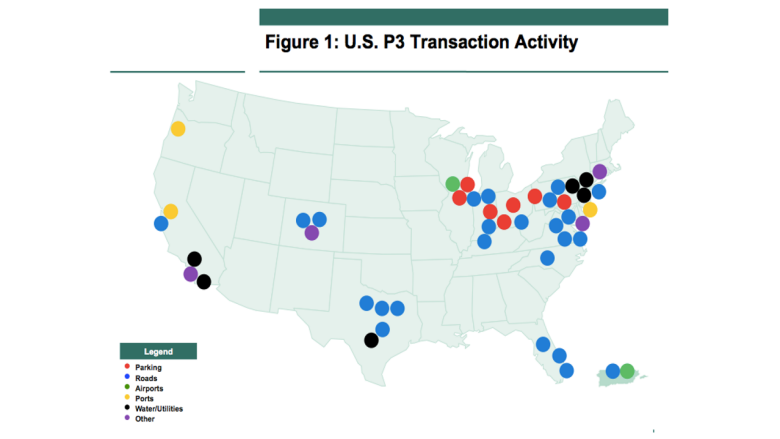

Overall, the U.S. PPP market has successfully transformed from its early days. Transaction structures have steadily changed as governments balance proceeds potential, risk allocation, project delivery costs, and other policy considerations. In this context, the current market for PPPs remains robust, as underscored by diverse transaction activity across the United States (see Figure 1).