Key insights & Data highlights

New technologies are affecting labor markets and the nature of work by displacing, augmenting or creating new tasks performed by workers.

Robots are displacing industrial workers in routine manual task occupations (e.g., assembly line operators).

AI threatens to displace services workers not only in routine tasks (e.g., risk assessors) but increasingly in nonroutine cognitive tasks (e.g., interpreters). AI-empowered robots could also impact workers in nonroutine manual occupations.

Both AI and digital platforms may lead to the creation of new tasks (e.g., AI-prompt engineers and cloud engineers).

Interact with the chart below by clicking on it to reveal the elements of the framework.

The task structure of jobs in EAP and advanced economies

The exposure (technical susceptibility) of jobs to new technologies in EAP countries differs from that in advanced economies.

Because EAP countries employ more people in occupations involving routine manual tasks and fewer people in cognitive tasks, they are more vulnerable than advanced countries to job displacement by industrial robots than to displacement by AI.

Full Report: English

Summary: English

The labor market impacts of new technologies

The extent to which new technologies impact jobs depends not only on their technical feasibility but also on the economic viability of adopting the technologies. A specific technology is economically viable if the cost is lower than the benefit from adoption.

Robots

In the EAP region, as robots have become economically feasible, their adoption has led to an increase in overall manufacturing employment. This is because the higher productivity from adopting robots leads to increased scales of production that offset the labor displacing effects of automation.

But the impacts of robot adoption are being felt differently across population groups. For instance, between 2018 and 2022, robot adoption helped create jobs for an estimated 2 million (4.3 percent of) skilled formal workers but displaced an estimated 1.4 million (3.3 percent of) low-skilled formal workers in five Association for Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries.

Full Report: English

Summary: English

AI

While it is too early to assess the labor market effects, AI is likely to also have both displacement and augmentation effects across occupations. The EAP region may be relatively less exposed to the displacement effects, but is also be less well placed to benefit from AI.

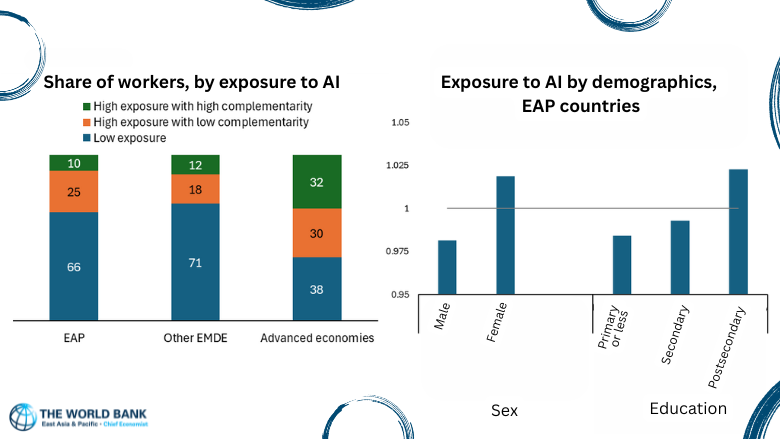

Only about 10 percent of jobs in the EAP region involve tasks complementary to AI. This share is similar to that in other emerging economies, but much lower than the 30 percent share in advanced economies.

Exposure to AI is not uniform across workers. In EAP, women and better educated workers are more exposed to AI than men and the less educated workers.

Economy-wide impacts of technology adoption

To assess the overall impact of technology on jobs, it is essential to consider the interdependence and impact of technology choices across sectors. EAP resembles the rest of the world in the labor market impacts of agricultural mechanization, but the impacts of industrial robotization have so far been different.

Mechanization is associated with farm productivity gains and little change in the level of agriculture employment. While the share of farm employment has shrunk globally and in EAP countries, this decline is driven more by the pull of higher manufacturing wages than by mechanization’s labor displacement.

In contrast, the share of manufacturing employment globally rises in the early stage of robot adoption and then falls. Developing EAP countries have so far defied this pattern. The share of industrial employment has continued to rise even as countries deepen robot adoption.

Full Report: English

Summary: English

The role of policy

Digital skills would equip people to engage with an increasingly digitalized workplace, using digital devices, applications, and digital platforms.

Social and emotional skills would give people a comparative advantage over machines in tasks that involve social interactions, from education to health care.

Advanced technical skills would enable people to work in the use and creation of these new technologies.

Labor mobility is impeded by market failures and policy distortions.

The former include poor information about job opportunities, underdeveloped land and housing markets, and inadequate connectivity. The latter comprise rigid labor market institutions and the inadequate portability of benefits.

Across a range of developed and developing economies, the stock of industrial robots (per 1,000 workers) is negatively associated with the relative taxation of capital and labor.

Favoring capital over labor can lead to excessive automation and suboptimally lower employment.

Removing distortions would shift the adoption of automation technologies closer to what is socially optimal and raise employment levels.

The need to develop schemes to offer social protection for workers outside of regular social insurance systems has become more pressing with the growing prevalence of gig work. For instance, self-employed gig workers in Malaysia are willing to accept a slight reduction in their incomes in exchange for regular contributions to social insurance schemes, such as unemployment insurance and pensions.

A range of schemes across the world, from public initiatives (in Colombia and India), public-private partnerships (in Malaysia), and purely private initiatives (in Denmark), have successfully applied a variety of approaches, including informing workers about the existence and benefits of schemes (as in India), financial incentives (as in Colombia and Malaysia), and behavioral nudges to offer social insurance to informal workers.