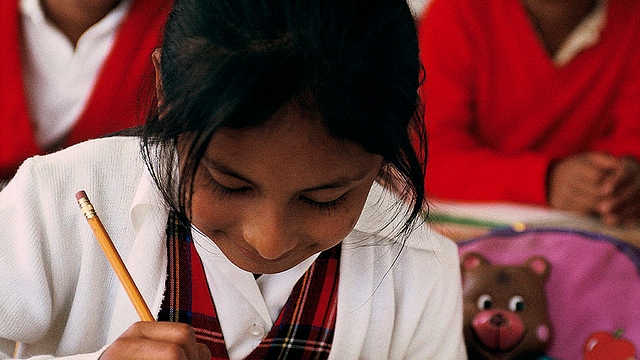

Many public schools in Mexico are failing to educate students, particularly schools in poorer areas. Recent tests show that most 15-year-olds do not have basic competency in math, and almost 20 percent do not have basic reading skills. Reforms to improve education in Mexico move slowly, and parents rarely have a voice. This research evaluated the impact of Christel House de Mexico, a low-cost, rigorous private school for poor children that also works to ensure parental commitment.

| Research area: | Education |

| Country: | Mexico |

| Evaluation Sample: | 172 poor first-grade students in Mexico City |

| Timeline: | 2013 – 2016 (Completed, endline report pending) |

| Intervention: | education, subsidies |

| Researchers: | Lucrecia Santibañez, Claremont Graduate University; Juan E. Saavedra, University of Southern California; Raja Bentaouet Kattan, World Bank; Harry A. Patrinos, World Bank |

| Partners: | Christel House de Mexico; The World Bank |

Emerging economies need quality education systems in order to improve their competitiveness internationally and develop high-skilled industries. Often, government-run schools are slow to catch-up with the demands of these developing economies, which in turn can slow or even depress growth. Schooling for low-income or otherwise marginalized groups can be an even bigger challenge, and without changes those most in need can be left out or unable to take advantage of opportunities to find productive work. This evaluation, which looked at the impact of subsidized private education in Mexico specifically for poor students, provides evidence about the effectiveness of these education models as a route for reaching disadvantaged students.

Context

Like many other developing and middle-income countries, Mexico seeks to shift its economy from labor-intensive to one that relies more on knowledge and technical know-how. Doing so requires an educational system that can successfully teach students and produce graduates who are ready to move into non-labor intensive work or go on to higher education. But Mexico’s public education system is not meeting these demands. High school graduation rates are low, and standardized test scores are below those from other middle-income countries. Less than half of children who start first grade will complete high school. In Mexico City, reform efforts have faced tremendous opposition, particularly from the teachers’ union. The problems of educational quality and achievement are especially acute for disadvantaged students. Private schools that offer services beyond education are emerging as an alternative, especially for poor and otherwise marginalized students.

This evaluation investigated whether a private, affordable comprehensive school for poor families – in this case, one supported primarily through philanthropic donations -- can be a model for improving Mexico’s educational system.