Findings & Lessons from the 2017 Public Health Sector Expenditure Review

UNICEF and the World Bank’s Health, Nutrition, and Population (HNP) team conducted a detailed Public Expenditure Review (PER) for Lesotho’s health sector covering a five-year period from fiscal years (FY) 2011/12 to 2015/16 (in Lesotho, the fiscal year runs from April 1 through March 30). As part of the expenditure review, the World Bank and UNICEF collaborated with the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Development Planning, and the Ministry of Health, with support from a team of senior health economists from the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI), to undertake a data mining exercise and review all government health expenditure.

In the first chapter the PER provides a brief overview of health outcomes achieved, coverage of essential services, issues of financial protection, human resources’ deployment, and infrastructure available at different levels of care. In the second chapter, the PER analyses in depth financial flows within the health sector, including public and donors’ expenditure, illustrating expenditure dynamics over time, breakdown of expenditure by inputs (economic classification), by geographic location, by level of care, by cost centres and by type of facility (hospitals and primary care centers). Absorption of the budget over time, and efficiency and equity issues are also investigated.

The expenditure review paid special attention to expenditure for outsourced health service providers, such as Tsepong (the operators of QMMH and its clinics) and the Christian Health Association of Lesotho (CHAL), which operates over 20% of the primary health centers and 40% of the hospitals in Lesotho, and in Chapter 3 the PER investigates in detail issues concerning the affordability of the QMMH PPP for the Government of Lesotho.

General Health Sector Findings

A number of major health outcomes have shown minimal improvement in the period: By looking at key health indicators, such as infant mortality (IMR) (59/1000 livebirths), maternal mortality (1,020/100000), one can see that health outcomes are still extremely poor in Lesotho, despite significant investments in the sector. Lesotho has the world’s third highest prevalence of HIV/AIDS (23.4 percent); and life expectancy is 54 years, a reduction compared to the level held in the late 1990s, mainly because of the HIV AIDS epidemic. Malnutrition is an acute problem, with a prevalence of stunting of 40 percent. Over the past few years, significant effort has been made by both the GoL and partners to strengthen health systems related to maternal and neonatal care. While all these initiatives have strengthened health delivery, significant gaps remain. For example, the national rate of institutional deliveries has substantially increased between 2009 (42 percent) and 2014 (77 percent); however, changes in the MMR have been insignificant during the same period, suggesting inadequate quality of interventions that reduce mortality (mainly because of staff lack of preparedness, and staff and supply shortages at health centers). The 2015 Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric and Newborn Care (CEmONC) assessment reports that only 30 percent of the 20 secondary hospitals in the country (where nearly half of the institutional deliveries occur) provide all expected CEmONC services to ensure safe delivery, and 89 percent of maternal deaths occurred at facilities without CEmONC certification. Clearly, improving quality of essential services, such as safe deliveries, immunization, and postnatal care, needs to become an absolute priority.

Dearth of qualified and uneven deployment of front line health workers is an unresolved challenge: The ratio of doctors to the population is 0.9 per 10,000. For nurse-midwives, the ratio is 10.2 per 10,000. Both ratios are below the WHO AFRO regional average of 2.6 and 12.0, respectively, a poor result that has significant negative effect on the ability of the government to deliver quality health services. Allocation of resources and staff is biased in favour of Maseru, and thought should be given to reallocating doctors to underserved districts to ensure patients have sufficient access. Nurses are more evenly distributed among facilities due to the prevalence of many nurse-staffed primary health centers across Lesotho operated by the government as well as CHAL. Staffing needs to be aligned to each facility need and patient demand, as the current staffing process leads to both short-staffed, high-volume health centers and over-staffed/under-utilized, low-volume facilities.

Financial protection: Overall Lesotho has achieved good levels of financial protection, much better than other Sub Saharan African countries. There is an appropriate level and growth of investments in the Health Sector by Government and Donors: Lesotho’s total health expenditure is 10.5 percent of GDP, higher than many countries in the SADC region and around double the level for Sub-Saharan Africa. Private expenditure (mainly out-of-pocket expenditure) is 24 percent of the total, at only 2.5 percent of GDP; government is 44 percent; and external (financed by donors/development partners) is approximately 32 percent of total expenditure. Yet recent studies point to several barriers still discouraging health facility attendance. In rural areas, over 30 percent of deliveries still take place at home.

Evidence-informed policies: It is essential to improve the quality and availability of data for decision makers. At present the Lesotho Ministry of Health has a dire lack of data systems that are essential for addressing the major bottlenecks in the country’s health system. The Ministry of Health with the support of the development partners needs to urgently set up baseline measurements for key performance parameters for all primary care centers and hospitals, including those that are publicly-run, independent, or privately operated. These measurements need to be continuously monitored and updated, and will be used for planning, resource allocation purposes, and to increase accountability.

Need to improve budget execution at all levels: A key finding of the expenditure review is that over the last few years the problem does not seem to have been a lack of money for the health sector, but the wide differences in the ability of different parts of the health system to use the budget they are given. The Government of Lesotho’s recurrent health expenditure has increased nominally by 12.63% per year, and these increases are being distributed across the health sector, with large nominal increases for Laboratories (126%), Planning (163%), and Pharmaceuticals (162%), and payments to CHAL increasing by 121% during the period studied. Increases for government-run District Health Management Teams (135%), which deliver primary healthcare services and manage primary health care centers in 10 districts, is especially significant given the government’s emphasis on allocating more funding to districts to aid decentralized health service delivery. However, the utilization of these funds has been problematic across many cost centers, meaning the benefits of this funding are not being transformed into improved health outcomes. For example, district hospitals on average used 90% of their budget, but this average hides sharp differences. For example, Mafeteng Hospital consistently used about 95% of its budget during the period studied, while Machabeng Hospital used less than 70% of its budget. In terms of absorptive capacity, District Health Management Teams, responsible for financing primary care centers, performed worse than district hospitals, on average only spending around 80% of their budgets. Some DHMTs struggled to use even 65% of their funding in any given year.

The main priority for the Ministry of Health should be to strengthen its control systems both for compliance, as well as performance, at all levels (center, district, facility level), which now appear extremely weak. The findings of the PER illustrate a fragmented health system with several pools of resources from donors and government, with different service providers operating according to different priorities and operating mechanisms, and without any accountability for results. Addressing the under-utilization of health funds and increasing efficiency in health sector management should be a priority for the Government of Lesotho. This would help increase healthcare services by making full use of the Ministry of Health’s existing fiscal resources.

QMMH Health Network PPP Findings

Lesotho’s QMMH Health Network PPP: After a decade-long planning effort, Queen ‘Mamohato Memorial Hospital (QMMH) opened to serve the people of Lesotho on October 1, 2011. The QMMH hospital, along with four primary care clinics, makes up the QMMH Health Network, which was structured and tendered as a public-private partnership (PPP) in 2009 to replace the aging national referral hospital, Queen Elizabeth II (QE2).

Health Outcomes in the PPP: Hospital health outcomes improved quickly and dramatically with respect to the QE2 hospital QMMH substituted: studies carried out at QE2 (2007) and QMMH (2012) showed that QMMH provided vastly improved health outcomes for Basotho, including:

· 65% decline in paediatric pneumonia death rate

· 50% decline in stillbirths across QMMH and its four clinics

· 17% decline in hospital deaths within 24hrs, indicating better access to life saving medicines, surgery, and emergency care

· 10% decline in maternal death rate

Additionally, because QMMH includes a neonatal intensive care unit, which QE2 did not have, over 70% of very low birth weight infants have survived in Lesotho since QMMH opened its doors, virtually all of whom would have died before. Hospital data shows that 2,323 very low birth weight babies survived birth between January 2015 and August 2017, or 77 infants a month, most of whom would not have survived before QMMH opened its doors. As a result, over 10,000 extra live births have been successful since the QMMH health network began operating.

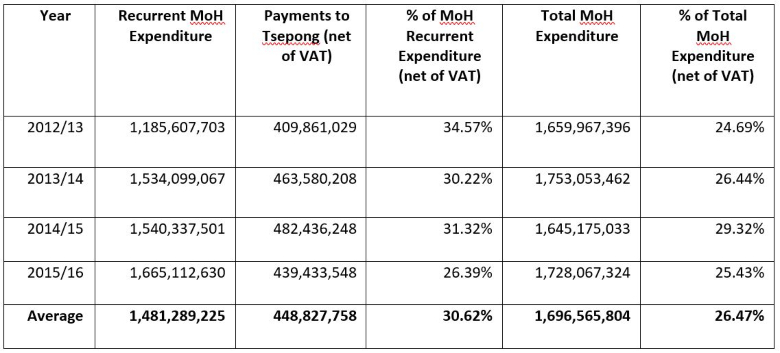

Government Expenditure on QMMH: Since QMMH started its operations, it has absorbed on average 30.6% of recurrent Ministry of Health expenditure (the amount set out in the annual budget) and 26.5% of total MoH health expenditure. The expenditure review found that this percentage has been fairly stable. However, the Ministry of Health has not paid all amounts invoiced by Tsepong. Since FY 2013/14, the amount paid by the government has been lower than the amount invoiced by Tsepong and the difference is highest for FY 2015/16. If all invoiced amounts are included, Tsepong has absorbed on average 33% of the Ministry of Health’s recurrent budget and 29% of total health expenditure over the past five years. Payments to Tsepong include a monthly Unitary Payment that covers the expected operational costs of treating up to 310,000 outpatients and 20,000 inpatients annually – as well as fees for providing care to extra patients over the 310,000 and 20,000 agreed to in the PPP agreement, transport, interest on late payments, and other smaller items.

Table 1: Proportion of recurrent and total MoH expenditure accounted for by net payments to QMMH

Source: Calculations based on accounts provided by MoF, MoH, and Tsepong.

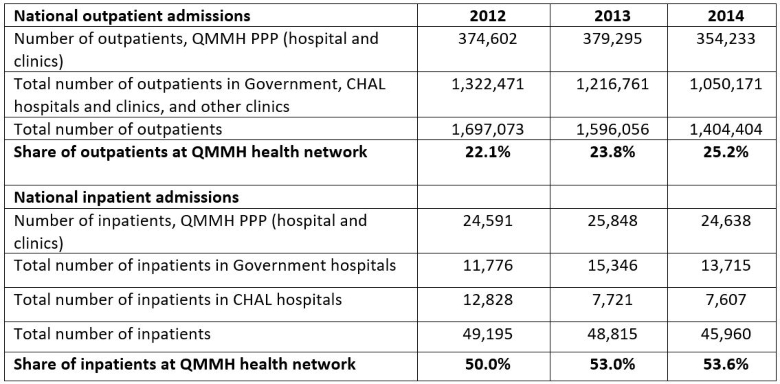

QMMH Cost and Service Volumes: To understand if the QMMH health network is providing value for the percentage of health expenditure it receives, it is important to identify how many patients are being provided healthcare through the network. The data below shows that the QMMH health network has provided healthcare services to over 50% of all inpatients in Lesotho annually, and has been treating one quarter of the country’s outpatients.

Table 2: Share of patients in Lesotho cared for through QMMH PPP

Source: Ministry of Health, Planning Unit, CHAL accounts, Tsepong.

QMMH Health Network Sustainability: The QMMH PPP has been a source of opposing views since its inception, with some of its advocates pointing at positive clinical results and efficiency gains, and detractors emphasizing its cost trajectory. Overall, the evidence provided by the public expenditure review suggests that the QMMH health network has been fiscally sustainable for the Government of Lesotho throughout the period studied.

Ongoing Challenges: Despite being fiscally sustainable, the QMMH health network still faces several challenges that must be addressed. There are significant payments for extra services that have been invoiced by Tsepong, but not yet paid. In addition, there are several matters that are now subject to arbitration because the government and Tsepong disagree on the payment terms and amount. These include, unpaid invoices for extra health services and interest charged on late payments, the annual inflation rate for patient tariffs, and the raise in health workers’ salaries in 2013.

Delivering on MoH Objectives: A broader issue is whether QMMH is performing the function which was originally envisaged for the new hospital, which was to become the premiere tertiary healthcare institution that all Basotho people could rely on for their most difficult and urgent health conditions. At present, this vision seems far from being implemented. The 20 secondary district hospitals in Lesotho have a combined hospital bed capacity of 1,833 beds, but their bed occupancy rate is alarmingly low, averaging just 32%, while the occupancy rate at the 425-bed QMMH was 74% during FY 2015/16. This evidence suggests that district hospitals are not performing their function of treating less complicated cases (for example, deliveries without complications), and filtering patients that genuinely need tertiary treatment at QMMH. As a result, QMMH ends up seeing relatively simple conditions that could be more efficiently treated at lower levels in the health sector if the lower levels were functioning properly.

Lessons from QMMH PPP

There are a number of lessons worth highlighting, both from the findings of the expenditure review, as well as from the challenges the QMMH health network has encountered in its five years of operation.

First is that health PPPs should be integrated into the health system more effectively for it to meet government objectives and help drive improvements in the rest of the health system. In Lesotho, the QMMH health network appears isolated from the rest of the system when it comes to the broader management of public health sector, which is highly under-performing. Patients are not treated in the right facilities and at the right level of health care in the country, and too many patients with relatively simple conditions are being referred to the QMMH health network, or are self-referring, which has contributed to the cost of paying for the extra services being provided through the QMMH health network. The current contract did not envision the scale of this over-demand and poor referral systems and could have included a cap on payments for extra services to reduce the financial risk for the government. This should be considered for other health PPPs in environments where referral systems are inefficient.

Another key lesson is the need to build and maintain government capacity to manage a PPP, and to monitor and enforce the terms of the contract. PPPs do not eliminate, but rather change and intensify, the need for a government’s continuous involvement in monitoring the operator’s performance. In Lesotho, capacity and continuity issues have been a consistent problem for the government. Many of the issues under arbitration may have been avoided or resolved earlier if the contract management capacity needed to manage the partnership and identify and resolve issues quickly had been sustained. This same lack of monitoring performance and the use of finances applies to all outsourced health services in Lesotho, some of which are fiscally significant, such as CHAL. In FY 2015/16, the Ministry of Health maintained “subvention arrangements” or PPPs with 10 separate non-governmental healthcare providers, paying over US $60 million (LSL 869.6 million). It is critical in cases like Lesotho to provide continuous support in contract management, especially when government personnel turn over regularly and capacity is lost.

Addressing some of the core bottlenecks in it health system identified through the expenditure review will help the Ministry of Health better achieve its long-term healthcare objectives and help deliver measurable improvements in the health of all Basotho.