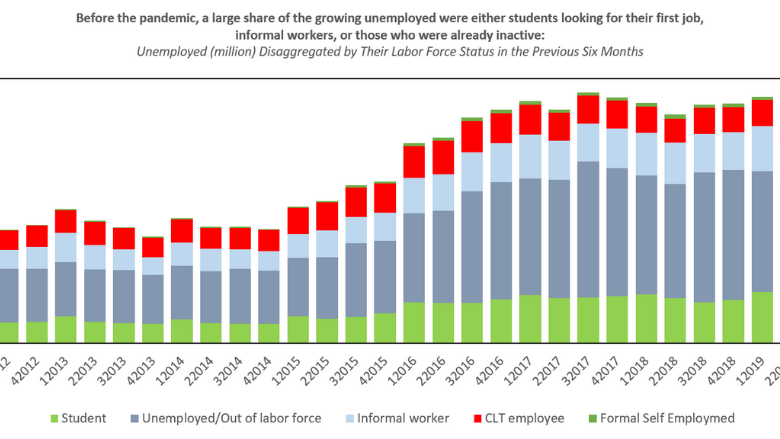

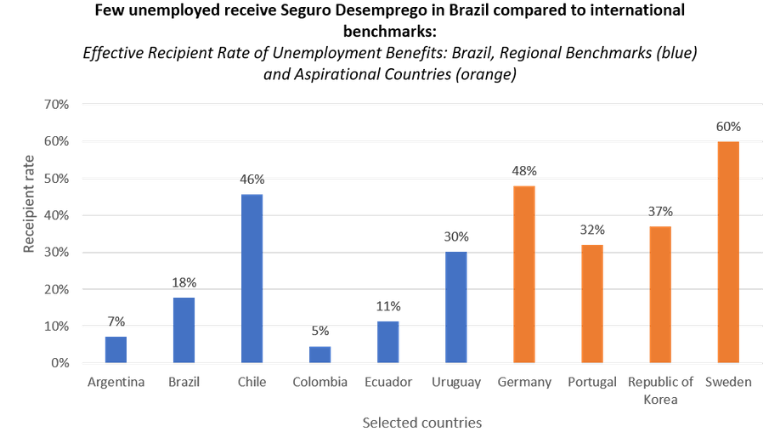

In 2019, prior to the pandemic, only 17.7 percent of the 12.6 million unemployed received unemployment insurance, well below the OECD average of 37 percent. Despite the low coverage, Brazil spends around 2.3 percent of GDP on labor market programs, most of which finances Seguro Desemprego (SD) and Fundo de Garantia do Tempo e Serviço (FGTS) withdrawals due to layoffs. The level of spending is high compared to any international comparator. The low coverage rate points to an outdated design of labor programs, which still assume formal dependent employment and cash-based assistance as the main ways to engage in the labor market.

The Covid-19 crisis reminded society that most of Brazil’s labor force is treated as “invisible”: the informal, self-employed and long-term unemployed, particularly youth, are ineligible for most labor market programs. Auxilio Emergencial became necessary precisely to address their vulnerability. The share of workers without protection could increase further during the recovery, as it happened after the 2014 crisis.

Source: Authors based on PNAD Continua 2012–2019.

Note: The figure shows the labor status of the unemployed two quarters before any given period.

What could improve the protection of the Brazilian workforce without increasing contributions from employers or government? A recently released World Bank report benchmarks Brazil’s unemployment system with international comparators, and sheds light on several avenues to improve both equity and efficiency. Comparisons were made with best practice countries (Germany, Portugal, Republic of Korea and Sweden) and also regional peers (Argentina, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador and Uruguay).

On average, SD replaces 80 percent of the workers’ wage before dismissal, with peaks of 100 percent at the minimum wage. This is above all comparators considered in the report. A second peculiarity of Brazil is that FGTS and SD are paid simultaneously, leaving many dismissed workers with a higher payout in the first month than when working.

In contrast to its generosity, the payout of SD (three to five months) is shorter than in almost all other countries. Further, the minimum employment period to access the benefit for the first claim (12 months out of last 18) is longer in Brazil than elsewhere. Poorer workers who, on average, retain a formal job few months a year, have limited access to this protection instrument, while, paradoxically, access to SD becomes less stringent for repeated users.

Source: Authors’ based on ILO Social Security Database 2019, OECD Social Benefit Recipients Database (SOCR) 2016 and IPEA data.

Note: The numerator of the rate is equal to the average monthly number of beneficiaries of unemployment insurance benefits. The denominator equals the total number of monthly unemployed (OECD SOCR, 2016). The rates correspond to 2016 numbers. For Brazil numbers have been updated to 2019 values.

An established literature showed how these badly designed incentives results in unnecessary claims, or ‘waiting out’ until benefits are exhausted. At the same time, the relatively short program does a disservice to those genuinely at risk of long-term unemployment.

To combat abuses of unemployment benefit, most countries monitor recipients’ autonomous job search and participation in proposed job interviews. While Brazilian legislation includes these elements, in practice, few SD recipients participate in job interviews organized by the Sistema Nacional de Emprego (SINE). Poor enforcement is ultimately tied to years of underfunding of SINE (less than 0.01 percent of all expenditures in Fundo de Amparo ao Trabalhador in 2020 (FAT)). The budgetary projection for FAT in the period 2021-2024, once confirmed, may represent a first positive reversal in this trend.

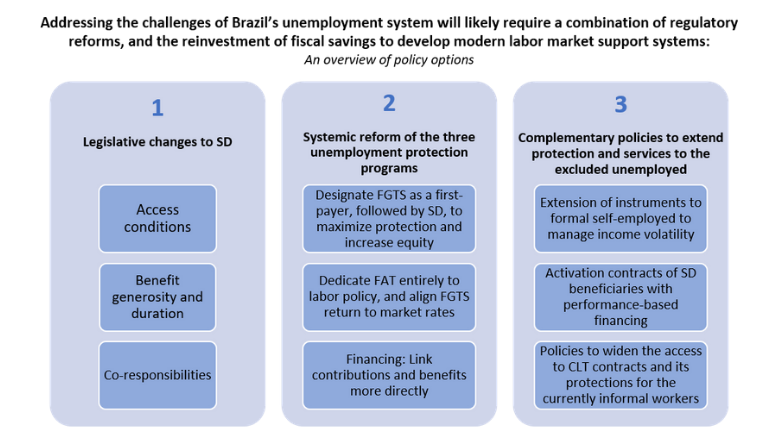

Increasing protection for more Brazilians from future labor market shocks will require a reform to existing unemployment programs, coupled with policies to increase formalization, extend protection to the self-employed, and provide active labor market services for displaced and unemployed workers.

In order to align with international best practice, particularly in countries with large informal sectors, FGTS could be designated as the ‘first payer’ of income support after dismissal, distributed on a monthly basis, and SD could be paid when income from FGTS is depleted. The unemployment benefit could be reduced, while the maximum benefit duration increased.

To increase access to SD for those with intermittent careers, the number of months to be eligible for the first-time claim could be reduced, while requirements for subsequent claims increased. Simulations suggest that these systemic changes results in shorter average unemployment duration and a lower deficit of FAT, which is the financing source of SD. A previous World Bank publication fully illustrates this reform.

The resulting fiscal space could finance a portfolio of modern services and policies. For instance, evidence shows that when well-designed, skills development programs have lasting effects on workers’ re-employment potential, and it protects them from future shocks.

Labor market insertion of low productivity or inexperienced unemployed can be promoted through targeted wage subsidies (as the “Contrato Verde Amarelo” proposed), as well as through simplifications of labor regulations (which differ from deregulation) that reduce employers’ uncertainties. To protect the growing number of self-employed, Brazil could explore instruments for financial self-insurance, through individual savings accounts that exploit behavioral nudges and tax incentives.

As in most countries, introducing changes to labor market programs is politically complex. The COVID-19 crisis laid bare the limitations and inequities of the status quo, and may be the opportunity to renew the social contract for a twenty first century labor market system.

Related links:

See full note in English: Enhancing Coverage and Cost Effectiveness of Brazil’s Unemployment Protection System: Insights from International Experience

See full note in Portuguese: Aumentar a Cobertura e a Eficiência da Proteção ao Desemprego no Brasil: Aprendizados da Experiência Internacional

See blog post published in Folha de S. Paulo: O Brasil pode oferecer um sistema mais inclusivo de proteção contra o desemprego?