I recently moved back to Russia after spending more than two decades away – and I found a country quite different from the one I left in the late 1990s. The development journey that Russia has undertaken since that time has been nothing short of remarkable. Yet critical challenges remain, and the World Bank’s mission is to help Russia fight poverty and achieve shared prosperity by addressing these challenges one by one.

Like several other countries around the world, Russia faces advanced population aging, along with declining fertility and mortality in the decades ahead. The long-term social and economic impacts of these changes will be significant, affecting labor markets, health and pension systems, and economic growth.

Russia’s population peaked in the early 1990s at about 148 million people, but, based on current trends is expected to decline to 136 million by 2050, due to low birth rates and relatively high mortality. And, while life expectancy in Russia has increased from 67.9 to 72.9 years over the last 10 years, it remains well below the OECD average of 80.6 years.

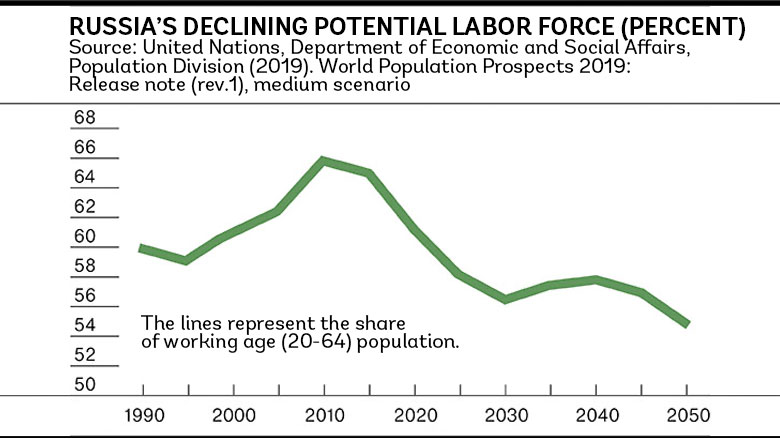

Most critical, however, is the rapid aging of Russia’s population that will occur over the next two generations. At about 15 percent, the share of people over 65 years in Russia is almost double the world average of 9 percent. And, according to the UN, the share of people over 65 will reach 23 percent in Russia by 2050, compared to the world average of 16 percent. Consequently, Russia’s potential labor force (share of population in the age 20-64) is expected to shrink from 61 percent of the population today to 55 percent by 2050.

The implications for Russia are important – countries with a rapidly shrinking working-age population often struggle to maintain the pace of physical and human capital accumulation needed for economic growth. Moreover, older societies tend to become more unequal, as health and life expectancy are correlated with education and income. This also has major implications for Russia’s place in the world.

But Russia is not alone in facing such challenges. So, what lessons can it learn from other countries?

The experiences of Japan, Sweden, and Finland, for example, can shed some light. Japan has the world’s highest proportion of population over 65 years, and has adopted a multi-pronged approach to addressing its demographic challenges.

One such initiative is to boost fertility, with policies designed to make having children easier, by allocating funds to new childcare facilities, reducing educational costs, and improving family housing. Russia is already active in this area. Another initiative is to increase female labor force participation, which includes a focus on technological innovation as a way to raise productivity, reduce caregiver burdens, and minimize healthcare costs.

And, given that healthier individuals are better able to continue working longer, programs have been put in place to protect older individuals’ health. Japan has raised its retirement age, which Russia also did recently, and is relaxing immigration restrictions to augment the size of its workforce.

Sweden has the world’s second-highest proportion of elderly people, and recognizes it needs greater numbers of migrants in order to meet increased labor demands. Sweden is also promoting active aging, including advancing how it deals with long-term illnesses.

Finland faces the enormous challenge of seeing its long-term growth rate drop to 1.5 percent, due largely to its rapidly aging population. As such, the country is finding innovative ways to manage long-term care, including by promoting self-managing facilities for the elderly, using modern technologies to expand remote care, and supporting its elderly through virtual nurse and doctor visits. Similar to Japan and Sweden, Finland is also looking to increase immigration to compensate for the sharp decline in its labor force.

What are the main takeaways for Russia, if it is to adequately address its demographic challenges?

First is the importance of immigration: in the high-income countries of Western, Southern, and Northern European that have rapidly aging populations, migrants help bolster the size of the working-age population and significantly increase the size of the labor force. Attracting migrants – especially high-skilled migrants – in the years ahead will be essential for Russia. Equally, this process needs to be carefully managed and adapted to Russian realities to avoid fueling social backlash to immigration.

Second, the importance of enhancing investment in the human capital of young people – their education and health – so that when they are adults they will be more productive and healthy citizens who could, at least partially, compensate for the decline in the share of the working-age population of Russia.

Third, the importance of active aging: while Russia has made significant progress in increasing life expectancy, what really counts is healthy life expectancy. Unfortunately, healthy life expectancy in Russia is 10 years below the average life expectancy globally. That’s why it is essential to keep people healthy through prevention and primary care. This will also help limit the country’s overall health costs.

Last, but not least, the use of technology is becoming evermore important in addressing the needs of an aging population. Russia’s focus on digitization today may offer similar opportunities to boost productivity and labor force participation, as is the case in both Japan and Sweden.

In the coming decades, as Russia experiences a major demographic transition, adjustments to policies and to individual behavior can significantly reduce the impact on labor force participation, the incidence of disease, and economic growth.

So, if a person were to leave Russia today and come back in 2045, they might find that it is thriving as a high-income country with a sizable labor force and reduced inequality – demography is not necessarily destiny if the right policies and behavioral changes are implemented.