As Tolstoy wrote in his timeless novel Anna Karenina, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Often referenced to explain how a shortage of just one of several factors can doom an entire effort to failure, this famous literary line could also describe the complexity of the challenge Russia faces today in reducing poverty.

Across this vast country, poverty levels vary widely – especially between urban and rural areas – from less than 8 percent in Moscow or Saint Petersburg to more than 20 percent in Kalmyk Republic or 40 percent in Tuva Republic. And, people can experience poverty in very different ways.

For example, a young couple with three small children in a remote village in Siberia might struggle financially due to limited job opportunities and meager state support. A middle-aged, secondary-educated person in a city in the Volga region might struggle to provide for their family because they lack the skills needed to find meaningful employment. An individual living in a Moscow suburb, taking care of a sick or disabled parent, might blame the high costs of medical treatment for their inability to pay the rent.

In Russia, poverty takes many forms, and its complexity hinders widespread progress in poverty reduction. That is why a business as usual approach will not suffice – instead, meaningful reforms are critical if Russia is to meet its ambitious goal of reducing poverty by half by 2024, as outlined in its National Development Plan.

We know that economic growth is a pre-requisite for reducing poverty, although growth alone is not enough. Strong growth from 2000 to 2011 helped reduce poverty from about 30 percent of the population to just under 11 percent during the same period, but the rate of poverty reduction has since stagnated.

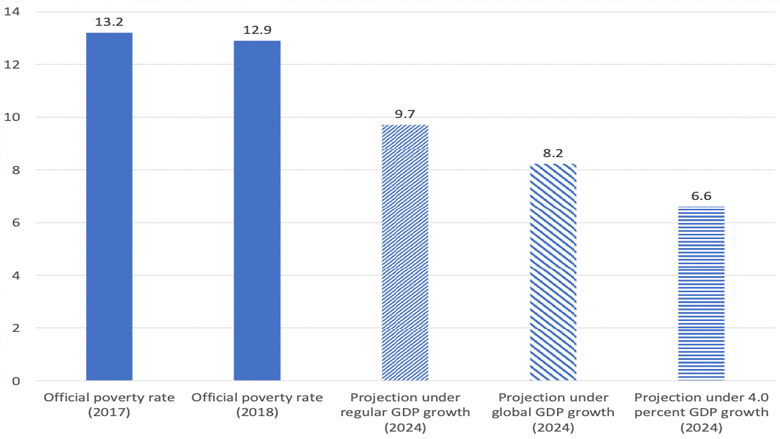

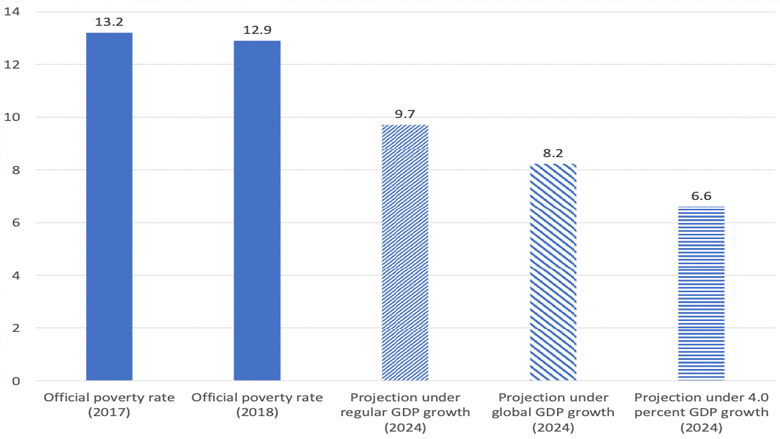

In fact, Russia’s poverty rate rose again in 2017, to 13.2 percent, and is projected to only fall to 9.7 percent in 2024, far short of the government’s target of 6.6 percent. To reach this target, the World Bank estimates that economic growth would need to surge to 4.0 percent, which is unlikely given current forecasts.

Although difficult, accelerating growth is not impossible. Our estimates show that Russia’s potential growth is around 1.5 percent – but implementation of the right policy reforms could boost it to around 2.5 percent by 2024. Indeed, we have seen similar growth accelerations in other middle-income countries in the past: Ireland in the early 1970s, South Korea in the early ‘90s, and Poland in the mid-2000s.

Which policy reforms could accelerate Russia’s growth?

To begin with, we recommend policies that favor higher investment and increased productivity. Russia has made some progress, but much more can be done. For example: policies that encourage greater competition would help combat distortions in the public sector; a better business climate would protect minority investors and resolve insolvency; and more emphasis on innovation could boost private investment in Research & Development.

Moreover, such policy reforms would benefit Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), and have a favorable impact on employment and wages – all essential for poverty reduction. The role of SMEs in Russia’s economy has certainly grown – representing 22 percent of GDP and 25 percent of total employment today – but still compares unfavorably with OECD countries, where SMEs represent 50-60 percent of GDP, on average, and 60 percent of employment.

At the same time, however, we must acknowledge that faster economic growth may not reach those individuals and families most in need. People working in the informal sector, or with limited schooling, or suffering from chronic diseases are more likely to experience poverty and to be excluded from participating in economic growth.

Poor families with children experience poverty rates well above the national average, and are most in need of effective social assistance. Targeted social assistance can play a critical role – in tandem with economic growth – in accelerating poverty reduction, but reforms should not focus only on transfers. The state needs to also actively prevent welfare dependency and incentivize beneficiaries to participate in economic activity.

Each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. For some people, the biggest challenge is a lack of job opportunities, or inadequate skills and training; for others, it’s access to affordable health care, or child support.

What does this mean for Russia’s policy makers? It means giving special attention to areas of the country utterly deprived of employment opportunities. It means ensuring everyone, young and not-so-young, has access to high-quality education and skills training. It means providing health care and child support that are accessible and affordable.

Russia has the resources – the budgetary means, as well as the administrative capabilities, to implement the necessary reforms. What it needs now is a comprehensive, integrated policy approach that leads to more inclusive growth for everyone in the country. After all – to borrow again from Tolstoy – Spring is the time of plans and projects.