One thing that stands out from my interaction with professionals who work on Russia, ranging from corporate executives to financial analysts, is this: most commit the mistake of treating Russia as a single unit of analysis. But Russia is a federation composed of more than 80 diverse regions. Treating it otherwise is like being unaware that a Matryoshka doll is not empty!

Russia’s regions fuel both the nation’s growth and equity outcomes. On the one hand, Sakhalin Oblast’s per capita output is comparable to Singapore’s while Ingush Republic’s languishes close to Honduras’. Regional poverty rates also range from less than 10 percent in resource-rich Tatarstan and metropolitan Moscow and St. Petersburg to almost 40 percent in the poorest regions in the North Caucuses, Siberia, and the Far East.

The World Bank recently published a report “Rolling Back Russia's Spatial Disparities: Re-assembling the Soviet Jigsaw Under a Market Economy”. Here are eight myth-busting findings:

Myth 1: Russia’s regional disparities can be compared with those in Australia and Canada

Truth: Russia’s regional disparities stem from its unique economic geography, which can’t be compared even to seemingly similar countries such as Australia and Canada. While the latter also have large land masses and even lower population densities, a large share of their populations live near the border or sea. In contrast, Russia’s people are more dispersed inland. Moreover, the populations of Australia and Canada are concentrated in major cities: more than two-thirds live in the three largest urban centers.

On the other hand, Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Nizhny Novgorod are home to only one-eighth of Russia’s population. Russia’s population decline, aging workforce, and need to adapt to a chain of economic shocks, have led to a spatial pattern of development counter to that found in other large countries.

These disparities can be accounted for by the Soviet legacy of a planned economy, demonstrated by the challenges facing Soviet-era industrial monotowns, the country’s diverse physical geography — Russia accounts for 11 percent of the world’s land mass but only 1.9 percent of its population – and its harsh climactic conditions, which impair transportation services.

What it means: A unique economic geography requires unique solutions.

Myth 2: Moscow and St. Petersburg are “too big”

Truth: To the contrary, these cities are not big enough. Moscow and St. Petersburg are the only Russian cities with a population larger than 1.5 million, while Japan, with its smaller population, has five such cities, and Brazil (50 percent larger than Russia by population) has eight.

Moreover, Russia’s second-tier cities are also not large enough. Cities ranked between 3rd and 10th by population only account for 6.6 percent of Russia’s population, a share that is well below that found in Brazil, Japan, and Poland, where cities in the same ranks account for 8 -11 percent of the respective populations. Russian cities are also not dense enough. The density of Russia’s 1 million-plus cities only ranges between 1,000–5,000 people per square kilometer, while in San Francisco and Lyon, the figure stands at 7,100 and 10,000 people, respectively.

Russian cities grow more by sub-urbanizing rather than by densifying, and poor policies contribute to this. For example, in the rush to meet federal housing construction targets, rather than pursuing meaningful densification, municipality permits are issued for housing developments in greenfield sites in peripheral city locations.

What it means: Russia will need to balance its urban system, shifting from two dominant cities and second-tier cities that are not large enough to affect regional development.

Myth 3: Russian regions are diverging in terms of income and poverty

Truth: Regions have in fact experienced convergence. While in 1998, regions were more heterogeneous in terms of real income per capita, this was reversed by 2008 and incomes continued to converge. Most regions also saw a large decrease in levels of consumption inequality between 2005-2015.

And encouragingly, poor regions grew faster than rich regions. But such convergence is slowing down: overall mobility in Russia declined from 3 percent per annum in the early 1990s to 1.2 percent by 2008. And due to the recent economic slowdown, federal transfers to regions – which were important in promoting convergence – drastically fell by as much as 22 percent in real terms between 2013 and 2016.

What it means: The convergence engines of integration of labor and capital markets, increases in working-age populations, especially in poorer regions, and federal transfers, need to be re-started.

Myth 4: Most of Russia’s poor live in poor regions

Truth: Actually, Russia’s richest regions house most of the country’s poor. While the percentage of people living in poverty is very high in poorer regions such as Tuva Republic and Kalmyk Republic (almost 35 percent), due to their small populations, they only account for 0.6 percent of Russia’s poor.

In absolute terms, because of their large populations, richer regions are home to a larger number of the poor despite their low poverty incidence; the cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg together account for almost 10 percent of Russia’s poor. Similar patterns are observed in other large countries such as Brazil and China.

What it means: It is not necessary to “balance growth” across Russia’s regions. Rather, the impetus should be on making richer regions “work” for the poor.

Myth 5: High potential regions are limited to Moscow and St. Petersburg

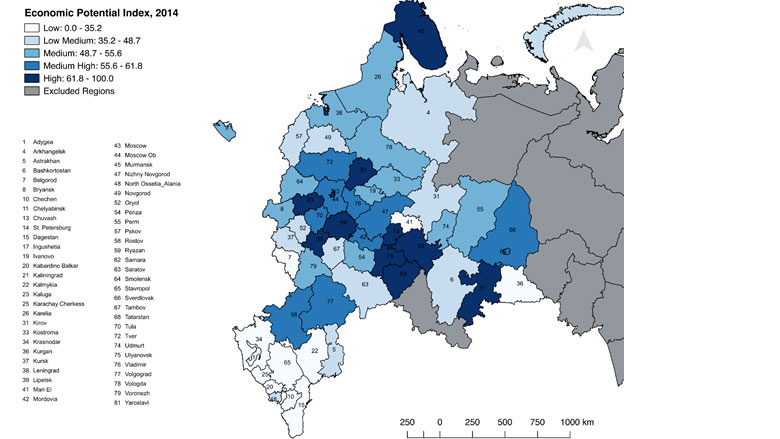

Truth: We identified three corridors of high-potential regions in Western Russia not confined to just Moscow and St. Petersburg by developing a new economic potential index for 56 regions in European-Russia:

- One corridor of medium-high and high potential regions radiates from Moscow and includes Yaroslavl, Kaluga, Ryazan, and Lipetsk Oblasts, who seemingly benefit from their proximity to major population centers and high rates of urbanization.

- A second corridor stretches from Rostov Oblast in the south to Tatarstan in the north and includes Volgograd, Samara, Ulyanovsk Oblast, and Chuvash Republic. These regions are densely populated, have large urban centers, a highly-educated population, and established industrial bases.

- A third corridor is found in the southern Urals, and includes Sverdlovsk Oblast and Chelyabinsk Oblast, regions that are highly urbanized and known for being the industrial heartland of Russia.

Murmansk emerges as a surprising, high-potential region, driven by its access to external markets given the number of ports and the volume of cargo transiting. The potential is also driven by its highly-educated population and high urbanization level, typical of the sparsely populated northern territories.

What it means: Natural resource wealth need not be the sole driver of regional development.

Myth 6: Isolated regions are isolated because of poor physical (transport) connectivity

Truth: While connectivity or access to markets (external and internal) is highly important for all Russia's regions, isolated regions (i.e., those far from markets in the European side of Russia) are not necessarily "transport-disconnected". Look at Zabaikalsky Krai, which is relatively well connected to its regional trade partners, including China, despite being far from Moscow and St. Petersburg.

What it means: The Far East needs to explore other aspects of connectivity. Given that last mile-connectivity is a perennial issue, digital and modern technology may help.

Myth 7: Reducing regional disparities is the job of either the federal or regional governments

Truth: On the contrary, it is the responsibility of both tiers of government: The federal government needs to provide more fiscal stability to regions, while also delegating more. It also needs to ensure its regulatory measures are aligned with regional contexts, to mitigate adverse impacts; the added cost of butchering, resulting from its 2014 sanitary regulations, put thousands of smallholder farmers in many regions at risk of bankruptcy.

Federal programs may also have complicated bureaucratic protocols; three years after its initiation, the Port Free Trade Zone in Ulyanovsk Oblast is still mostly empty. However, the regionally-managed "Zavolzhe" industrial park has attracted six large foreign investors. Differences between the two zones can be traced to the nature of federal legislation.

In turn, regions need to increase self-sufficiency. They could raise the corporate income tax rate to the maximum 17 percent, and accelerate the shift from book value to market value as the basis for assessing tax on corporate property. Fifty of Russia's regions offer some form of tax discounts to investors, which can prompt a race to the bottom. They can thus refrain from granting such exemptions.

What it means: this one is obvious!

Myth 8: Third party actors are not all that important

Truth: Credit rating agencies and international organizations already provide independent monitoring, assessment, and benchmarking of regions' performances. But their coverage and understanding of regions is limited; Fitch Rating Agency covered only 45 regions in 2017 and Standard & Poor's covered just nine.

To that extent, the Agency of Strategic Initiatives (ASI) can play a deeper role as rankings help identify and improve a region's investment climate. According to ASI, raising a region's investment score by 1.3 points is associated with a 1 percent rise in per-capita private investment.

What it means: Regions also need to be subject to market discipline, and third-party actors can expand their coverage and analysis of the regions. Their value-added will be enhanced if there are complementary reforms initiated by federal and regional governments.

I hope this article whets the appetite of readers to dive deeper into our work. Being originally from India – also a large and diverse country – and now privileged to work on Russia and its fascinating regions, makes me realize one thing: usually we fall in the trap of being unable to see the forest for the trees. But treating Russia as a single unit of analysis exposes us to its opposite: not being able to see the trees for the forest.

------------------------------

Originally published in Russian language in Forbes Russia (October 2018): http://www.forbes.ru/biznes/368743-preodolevaya-mify-chto-delat-s-neravenstvom-v-razvitii-rossiyskih-regionov