How much money have you spent in the past seven days? Have you skipped any meals in the past week? Is your child crying or talking more than usual?

How inclined would you be to answer these questions from a person you had never met before who knocked on your door? What if they came from someone calling your phone?

Getting objective answers — and checking to make sure they reflect the reality — is one of the biggest challenges faced by surveyors who gather the data that the World Bank uses to assess, for example, changes in poverty levels. The challenge got harder in early 2020 with the onset of COVID.

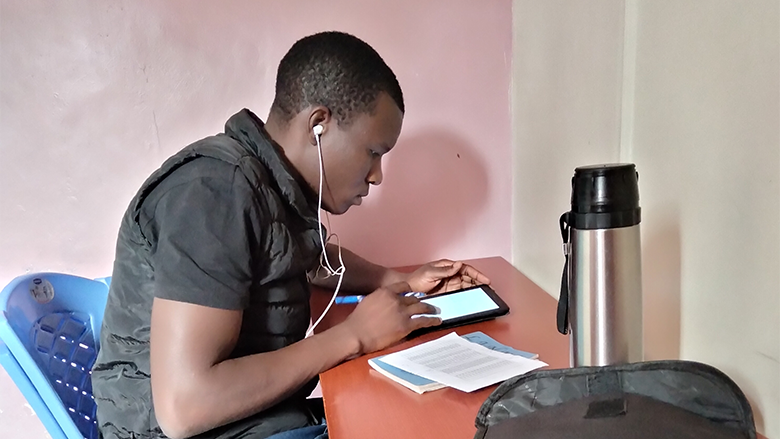

Lockdowns and social-distancing requirements made in-person surveys impossible in most places, triggering a fast-paced, unparalleled shift in how data is collected around the world. The surveys were typically done face-to-face by hundreds of surveyors — or enumerators, as these professionals are technically called – hired by World Bank partners across the world. They had to quickly migrate to phone calls, much more impersonal – and, well, suspicious to many.

“The transition was not small,” recalls Kevin Isiche, an enumerator in Busia, a small town in western Kenya. “The first challenge has to do with trust. In person, you introduce yourself, you have a badge. On the phone, some people think you’re a con. It’s much harder to build a rapport.”

The difficulties imposed by COVID-19 on tracking welfare were not limited to the field. Those ensuring that the methodology was sound and analyzing the survey results to draw a picture of the pandemic’s impact on households faced unprecedented challenges as well.

The World Bank had been conducting phone surveys for years, but the method was limited to special situations, when mobility or safety was an issue. They had been deployed in places affected by conflict or by epidemics such as the Ebola in West Africa, for example. COVID-19 gave researchers an opportunity to roll out phone surveys on a big scale — helping them understand their limitations and come up with ways to address these shortcomings.