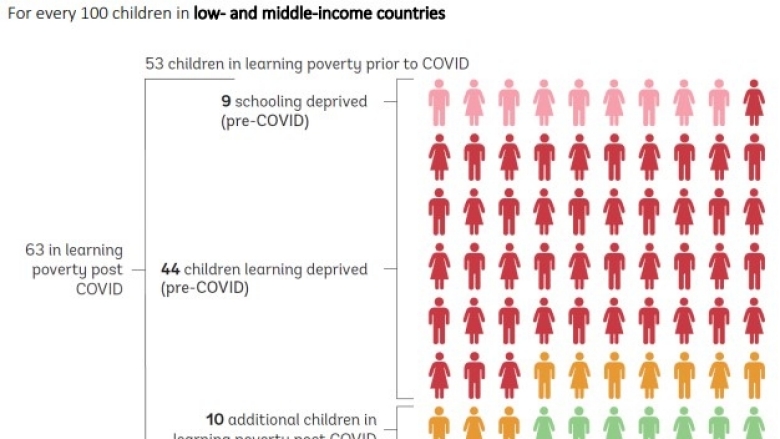

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Bank estimated that more than half of children in low- and middle-income countries were not acquiring the necessary foundational reading skills that underpin future learning. The pandemic has intensified this global learning crisis, with more than 100 million additional children estimated to fall below the minimum proficiency level in reading. In a post-COVID-19 scenario of no remediation and low mitigation effectiveness for the effects of school closures, WB/UNESCO simulations show learning poverty –the share of children unable to read and understand a simple text by age 10– increasing from 53% to 63%. The World Bank and UNICEF, together with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; U.K.’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO); UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics; and USAID, launched the Accelerator Program in late 2020 to tackle this urgent challenge.

The Accelerator Program aims to recognize and support a small, global cohort of governments that exhibit the crucial ingredients in the fight against learning poverty. By achieving success at-scale, Accelerator countries and states can offer inspiration to one another, exchange experiences on what works, and motivate other countries by showing how focused action and commitment can lead to quick improvements in the education sector.

The Program’s first ‘Accelerator Exchange Forum’ was held recently in which six Sub-Saharan African governments (Kenya, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria - Edo State, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone) introduced their approaches for tackling learning poverty. The sharing of experiences, lessons learned, and strategies –from the creation of “curriculum support officers” to engagement with parents to support home learning– is one way that the ambitious, multi-year Program aims to accelerate education reforms amid a global learning crisis.

With COVID-19 closing schools around the world over the last year, creating a deep socioeconomic crisis, Robert Jenkins, UNICEF’s Global Director of Education, said at the Forum that “in many countries, we are already beyond crisis state.” However, he also pointed out that the current crisis has put a sharp focus on learning, creating a “once-in-a-generation” opportunity to address these challenges.

The World Bank and UNICEF, with support from the U.K.’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO), UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics, and USAID, are responding with the Accelerator Program, which benefits from financial support from The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the World Bank’s new Foundational Learning Compact umbrella trust fund. Launched in October 2020, the Program provides financial and technical assistance to Accelerator governments that are reforming their education systems to rapidly improve the foundational learning outcomes of children. Ten countries or subnational entities have been designated as Accelerators (Brazil's state of Ceará, Ecuador, Kenya, Morocco, Mozambique, Niger, Nigeria's Edo State, Pakistan, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone) so far, but more countries are expected to be added over time.

Through the Accelerator Program, the World Bank will support (1) setting and monitoring key targets focused on improving foundational learning; (2) developing a realistic plan or investment case of evidence-backed, costed interventions to achieve those targets; and (3) strengthening the government’s capacity to implement the interventions.

UNICEF will work with the governments to provide the “glue” to the reform plans focused on: (1) communication and advocacy strategies to build knowledge and ownership; (2) analytical and advisory services to support access to global evidence and best practices; and (3) improved partner alignment and accountability around each country’s targets, reform plans, and implementation.

One of the cases presented in the forum, involving the state of Ceará in Brazil, illustrates how this approach can dramatically reduce learning poverty. One of the poorest states in Brazil with a population of 9 million, Ceará set a goal to ensure all students were literate by the end of second grade – and met its target by 2017. It implemented a plan based on a set of evidence-based policies that promoted foundational learning, including a focused curriculum aligned with teacher guides and learning materials that provided a clear routine for classes. Ceará also introduced accountable school management and used school assessments to monitor learning, with financial incentives cutting across these strategies. As an Accelerator country, it can provide useful lessons, even as the state seeks to build on its successes and address remaining and new challenges.

All Accelerator countries demonstrate a strong political commitment to education reform, and many have already initiated changes. In June’s online forum, education ministers and other government officials representing the six African Accelerator countries shared some of these initiatives. About 100 attendees participated in the invitation-only event, including Accelerator delegation members and representatives of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Children’s Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF), the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), the LEGO Foundation, U.K.’s FCDO, UNESCO, and USAID. Representatives of the governments of Finland, Germany, and Norway also attended.

The six Accelerators are at different stages in their reforms and can benefit from south-south exchanges along their reform journeys. The governments share several priorities: getting more children into school; ensuring a quality learning experience, especially through effective teacher training; and using evidence to inform policy decisions.

Addressing the latter, Joanie Cohen-Mitchell, Acting Deputy Director of USAID’s Center for Education, stressed during the Forum the importance of “strong feedback loops”, using evidence to inform policy decisions to ensure lasting positive change in the teaching and learning of foundational skills.

Governments have taken different approaches to boosting enrollment and improving learning outcomes. Rwanda works to ensure that the school environment is welcoming and that the children are learning, said Gaspard Twagirayezu, Minister of State, Primary and Secondary Education. In addition to opening over 600 new schools, the focus has been to train the 28,000 new teachers in those schools, provide them with teaching and learning materials and make sure they are comfortable with using the technology that is made available.

Mozambique is similarly focused on creating an environment that is conducive to learning with the focus on reading, writing and science, described Abel Assis, Permanent Secretary. The country is increasing the number of teachers and providing them training and will need to capitalize on the strong management and supervision of schools which has shown to improve the education outcomes.”

Other governments are also bolstering teacher training and support to improve service delivery. Nigeria (Edo State) has equipped teachers with 11,500 handheld devices and trained them on how to use the preloaded content for teaching. The devices allow officials to observe teachers’ lessons and give feedback, underscored Governor Godwin Obaseki.

Sierra Leone is investing in tablets for collecting data on teaching and learning, according to Emily Gogra, Deputy Minister of Basic and Senior Secondary Education.

Under Kenya’s Primary Math and Reading (PRIMR) Initiative, in addition to distributing textbooks to each child in grades 1–3, the government set up intensive teacher support and training, said Abdi Elyas, Director General of the Ministry of Education. The government replaced its Teacher Advisory Centers with “curriculum support officers” who each oversees a “zone” of 20 primary schools and support the schools’ teachers in the classroom. The officers use tablets to channel feedback on their visits into a central server, with the data used to improve teacher training.

These practices illustrate how Accelerator governments are demonstrating flexibility and shaping their policies based on evidence. For instance, Sierra Leone is using data from its 2020 digitized annual school census, which gathers information on enrollment, grade repetition, and students with special needs, among others, to make decisions on teacher hires and placement. “It helps us respond to needs on the ground,” said Conrad Sackey, Chairman of the Teaching Service Commission. “Without it, we are flying blind.”

Whether using technology or more traditional assessments, it is important for countries to have “adaptive and iterative learning processes based on data, evidence, and the needs of each child,” said Jenkins from UNICEF. Laura Savage, Senior Education Adviser and Deputy Team Leader of the Education Research Team at the FCDO said the U.K. is offering support to countries that want to “analyse, test, learn, and adapt approaches to ensure efforts to improve foundational learning are as effective as possible.”

Niger, where half of children are yet to meet minimum reading and writing requirements, is simplifying its school programs to focus on reading, writing, and numeracy skills, and providing additional support to pupils at-risk, stressed Rabiou Ousman, Minister of National Education. To improve accountability, heads of schools will sign performance-based contracts to ensure that the political commitment at the top cascades down to the school level. Such contracts typically link grants or other rewards to fulfillment of preset, verifiable goals.

Other countries are involving parents and communities. Minister Twagirayezu said Rwanda has sought to strengthen communication with parents, so they know how to support their children at home if the children are not reading well or come home with poor grades. Edo State Governor Obaseki said that sharing positive results from reforms with community members “can reinforce the political leverage you need to continue to drive the reforms.”

“A lot of things we need to do are not rocket science,” said Jaime Saavedra, Global Director for the World Bank’s Education Global Practice. The goal of the Accelerator Program is to “support [Accelerator] countries to improve [their] efforts at accelerated speed…so we can make a difference in the lives of our children today, and in learning in a relatively short term.”

In the next phase of the Program, the Accelerator governments, with the support of the World Bank and UNICEF technical teams, will set national learning targets and develop evidence-based costed roadmaps that will guide actions towards achieving the targets. Accelerators will participate in a community of practice to address common challenges, as well as share innovations and lessons learned throughout the Program.