Interview transcript – Mariana Felicio

Why is it that only 14 percent of women in Jordan work when 60 percent of non-working women sampled in a recent study say they would like to?

Societal expectations around women’s role in the household play an important part in keeping this percentage low. For women, getting married is one of the main reasons for leaving the labor market. Long working hours make it difficult for some women to juggle work, caring for children, and other household responsibilities. In part because of its flexible working hours, the public sector has traditionally been one of the largest employers of women in Jordan. However, job opportunities in this sector are decreasing and Jordan will have to rely on the private sector to increase female labor force participation.

A recent study co-led by Mariana Felicio, Senior Social Development Specialist in the World Bank’s Social Development team in the Middle East and North Africa Region (MENA), and Varun Gauri, Senior Economist in the Bank’s Mind, Behavior, and Development team (eMBeD), examines the specific reasons that may prevent women from accessing and actively participating in Jordan’s labor market, and the extent to which personal beliefs and social norms are a factor.

Why is this report so unique?

This is the first systematic representative study on social norms in MENA. It uses both qualitative and quantitative analysis for a more granular understanding of the extent these social norms influence women’s labor market participation. We asked questions around a) personal beliefs, preferences, and behaviors; b) expectations about how others should behave; c) the normative beliefs of others and their sanctioning behaviors. We also asked about the mutual expectations of male-female pairs in the family.

To which extent may social norms and personal beliefs limit (or not limit) women’s labor force participation in Jordan?

We wanted to understand the social norms around women’s employment in Jordan since it has the lowest female labor force participation in the world amongst countries not at war, and yet it has one of the most educated female populations in the MENA region.

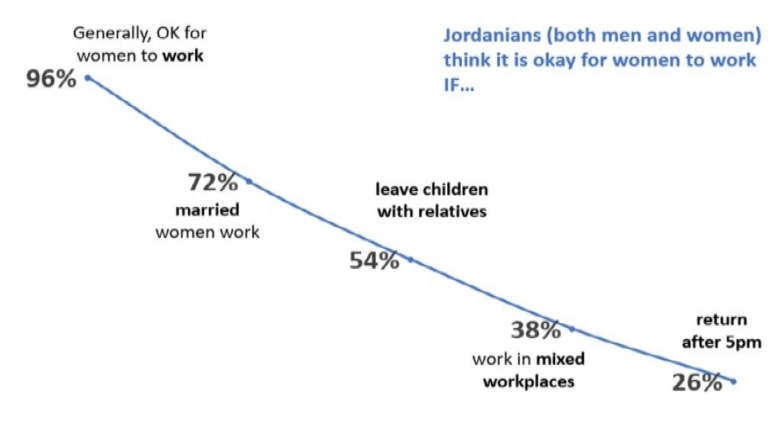

We were actually very surprised by the findings in this study. When we asked men and women: “Is it ok for women to work?” 96 percent said “Yes”. But when we asked more specific questions like “Is it ok for women to take public transportation?” or “Is it ok for women to hire a nanny?” or “Is it ok for women to come back home after 5PM?” the percentage dropped dramatically.

Only 26 percent of men and women believe it is okay for working women to return after 5pm. This explains the high demand for public sector jobs, as women can be back home by 3pm, which is less common in the private sector. In Jordan, working in mixed work places is also an issue. This is surprising since Jordan is perceived as less conservative among countries in the MENA region.

Contrary to common inferences delivering from labor statistics 60 percent of non-working women sampled for this study expressed a desire to work. We also found that women’s preferences and personal beliefs are not a major obstacle to their participation in the labor market, and they would likely respond positively to policies that address some of the most common binding constraints, such as lack of flexible work options, and scarcity of attractive jobs. In terms of making decisions in the family, we learned that men and women surveyed agree that the man is the ultimate decision-maker. Consequently, women who have a supportive man in the family are more likely to work.

There is a clear discrepancy between the perceptions men and women have of each other’s preferences, and their actual preferences. For example, women tend to underestimate the impact male family members have on their choices: 35 percent of women think their husbands would disapprove of them working in a mixed gender environment when in fact 60 percent of men admitted they would disapprove; 42 percent of the men surveyed believe that women prefer to stay at home to take care of children and the household, when in fact 37 percent of women said they prefer to do so. Both men and women prefer not to work in mixed gender environments, especially because of concerns it would expose women to harassment. Men expressed concern that women wouldn’t know how to handle such a situation.

What can the World Bank do to account for these lessons?

The World Bank Country Office in Jordan was very supportive of this work from the very beginning. As we finished the study, they were finalizing negotiations for a US$500 million five-year multi-sectoral reform, the First Equitable Growth and Job Creation Development Policy Financing operation. The sectoral teams of the loan worked closely with us to translate these findings into actions. For example: increasing employment opportunities in different sectors by offering part time and other flexible work options to increase female labor force participation. The loan also includes as a prior action the approval of a Bylaw on Flexible Work, encouraging contracts other than full-time work to encourage growth of formal part-time female workers. Other measures include improved efficiency and safety of public transportation, increased affordable childcare options, and better data on the share of women in the labor force and those employed in the private sector.

Through these measures and others, the multi-sectoral reform will help create a more enabling environment for women and promote economic empowerment.