When the prices of food staples surge, the food security of people around the world can be threatened in a matter of days. In 2007 and 2008, spikes in food prices pushed approximately 100 million people into poverty, according to Research Manager Will Martin’s analysis. However, it is important for policy makers to understand that the short-run impact of food prices on vulnerable populations does not present a complete picture of their long-term effect on poverty levels around the world.

Will Martin delivered this month’s Policy Research Talk, which focused on the topic of “Food Price Changes, Price Insulation, and Poverty.” The Policy Research Talks are a monthly event held by the research department to foster a dialogue between researchers and their colleagues across the World Bank. The topic of mitigating threats to food security is an important aspect of risk management and volatility.

Research Director Asli Demirguc-Kunt highlighted the complex policy implications of an increasingly integrated international economy in the context of the Bank’s twin goals to end extreme poverty by 2030 and boost shared prosperity. “Trade integration is an important catalyst of development, but it generates unequal gains. How should its distributional impact be managed?” she asked.

With co-authors Kym Anderson and Maros Ivanic, Martin’s research shows that in the short-run, the effect of price increases on welfare depends on whether households are net buyers or net sellers. Urban households are negatively affected, as are many farm households in poor countries, which are often net buyers as well; food price changes affect the cost of living and the value of output from the household business. In the long-term, increases in food prices lower poverty rates: Martin’s analysis indicates that it takes two to three years for price increases to translate into wage increases, but that the resulting increases in real wages for unskilled workers can be substantial. Ultimately, the effects are unequal, with rural households generally benefitting more than urban, which remain worse off after food price increases.

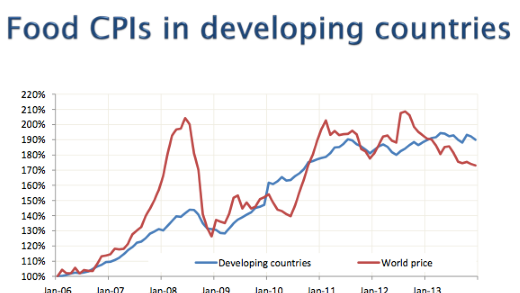

In his talk, Martin explored the political imperatives that drive agricultural trade policy. According to political economy theory, policy makers set the level of trade protection based on the strength of political support and the cost of protecting particular sectors. This protection tends to result in high average protection in rich importers and low protection in poor exporters. However, “the past few years of price volatility reveal something different: policy makers set domestic prices to insulate their countries against sudden price shocks, particularly for staples, but in the longer-term they pass through the changes in prices,” said Martin. Drawing on consumer price index data from developing countries compared to world prices, Martin demonstrated that while governments lowered import duties or imposed export barriers to provide strong insulation for rice and wheat prices—two politically sensitive food items—over the long-run, domestic and international prices converge.