World Bank

Papua New Guinea’s economy has been hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis due to weaker demand and less favorable terms of trade

Pandemic-related global and national movement restrictions have weakened external and domestic demand and affected commodity prices, which will lead to an economic contraction, wider financing gaps in the external and fiscal accounts, and higher unemployment and poverty than previously anticipated in 2020.

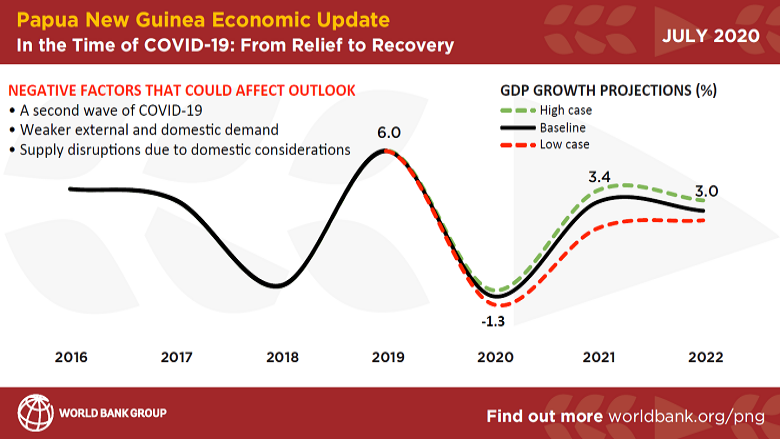

These updated projections for 2020 suggest that—compared to previous forecasts in January—real GDP growth will drop by 4.2 percentage points (to -1.3 percent), the current account surplus will decline by 11 percentage points (to about 15 percent of GDP), and the fiscal deficit will widen by 0.6 percentage points (to -6.4 percent of GDP).

At the same time, gold prices are at near-record highs, fuel import costs are falling, and Papua New Guinea is not highly dependent on foreign tourist income or remittances from abroad, softening the impact on the external accounts. Lower prices for liquefied natural gas (LNG) will have a limited impact on government revenues, as resource revenues remain small.

Australia, a significant trading partner, has also successfully contained the virus so far, providing hope that regional economic disruption will be lower than in Europe or the Americas.

The authorities reacted swiftly to the emerging external shock by developing a package of emergency health and economic relief measures

In early April 2020, the government mobilized its resources and appealed to development partners and the private sector for additional support to protect the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable households and businesses. The ensuing package of health and economic support measures totaled roughly PGK 1,835 million (about US$530 million or 2.2 percent of GDP) in 2020.

Reflecting the government’s limited fiscal space and anticipated revenue shortfalls, the health and economic support package will be financed by external concessional loans (PGK 670 million), foreign grants (PGK 65 million), and the use of employees’ savings in superannuation funds in job-loss cases (PGK 500 million). Commercial banks agreed to provide loan repayment holidays to affected households and businesses for three months (a package estimated at PGK 600 million).

The tax authority provided deferrals for tax filing and payment for two months and prioritized processing of goods and services tax refunds for medical supplies. The central bank injected additional liquidity into the system and provided foreign currency for COVID-19-related purchases of medicine and medical equipment.

While the focus of the authorities is currently on crisis mitigation measures, they should also look beyond the current year at a more robust and resilient recovery over the medium term

Real GDP growth is expected to rebound from a contraction of 1.3 percent in 2020 to an expansion of more than 3 percent in 2021.

Economic growth in the medium term will be supported by foreign investment in new resource projects, including the Papua LNG (liquefied natural gas) project, the Wafi-Golpu gold and copper mine, the P’nyang gas field, and the Pasca A gas condensate field. Potential expansions of the existing Porgera gold and silver mine (subject to its license extension) and the Ramu NiCo (nickel and cobalt) mine would also contribute to the impending investment boom.

However, considering that the economy entered the COVID-19 crisis with a poor record of resilience to external shocks, it will be vital to set the stage for more sustainable and inclusive development by strengthening macroeconomic management and accelerating structural reforms while protecting the vulnerable.

Special Focus: Investing in Physical Infrastructure for Sustainable Development

Providing equitable access to quality infrastructure is one of the most important ways a country can reduce poverty and enhance sustainable growth. By building and maintaining appropriate infrastructure, Papua New Guinea can work toward better living standards for its citizens and toward greater, more sustainable economic growth.

Electricity access in Papua New Guinea remains among the lowest in the world

The country has an abundance of natural energy resources—hydropower, natural gas, and solar—but they are underutilized: less than 250 Megawatt (MW) of its hydropower potential of 15,000 MW is harnessed, and the country exports liquefied natural gas but imports petroleum products to generate electricity.

Only about 13 percent of the population has access to on-grid electricity and about 25 percent to off-grid electricity. Even among those who have access, the cost of service delivery is high, and the supply of power is unreliable.

Network efficiency and safety remain a challenge for Papua New Guinea’s transportation infrastructure

About 35 percent of the population lives more than 10 km from a national road, and 17 percent have no access to roads at all, making aviation and maritime shipping crucial transport modes.

While the airport at the capital, Port Moresby, has been upgraded, the condition of the country’s other airports has deteriorated over time.

Communities without access to road and air travel rely on riverine and littoral maritime transport, but maritime and waterways infrastructure is mostly rudimentary and is dangerous for both passengers and cargo to use.

In recent years, there has been a gradual increase in the number of households with improved water supply, but overall access is still among the lowest in the world

As of 2017, 41 percent of Papua New Guinea’s population had access to safe drinking water—35 percent of the population in rural areas, and 86 percent in urban areas—but rural access to sanitation stood at 8 percent and urban access at 48 percent.

Limited access to improved water and sanitation services undermines public health and is a main contributing factor to PNG’s high infant mortality rate (39.8 deaths per 1,000 births in 2019).

In the current situation, poor access to handwashing facilities results in poor hygiene and impedes effective measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic.

The average incidence of diarrheal diseases in children (under five years old) in Papua New Guinea is 243 per 1,000, although in some provinces the number exceeds 500 per 1,000 children.

Access to information and communications technology (ICT) services has increased slowly in recent years and prices have fallen, though significant gaps remain

Eighty percent of the population lives within mobile coverage range, and the 3G network covers 40.9 percent of the population.

However, fixed and mobile subscriptions combined cover just 11.4 percent of the population.

Prices for ICT services, which have consistently ranked as some of the highest in the world, have declined in recent years owing in part to regulatory intervention.

There are four serious constraints to improving the stock and service quality of infrastructure in Papua New Guinea

- Papua New Guinea’s geography makes it difficult and expensive to build and maintain roads and other means of transportation. In turn, the lack of adequate transportation access makes it difficult and costly to provide energy, water and sanitation, and ICT infrastructure.

- In each of the sectors, a lack of policies and coordination, regulatory impediments, weak financing and investment strategies, and limited organizational and human resource capacity hinder infrastructure development.

- Papua New Guinea’s customary land tenure system makes it complicated to get an unobstructed title to the land needed for infrastructure.

- The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted a major economic downturn, reduced business activities and heightened affordability constraints, weakening the financial sustainability of energy, ICT, and water service providers.

In spite of these constraints, there is also much to build on. The abundance of natural resources provides the country with significant financial means

In the energy sector, for example, the government has set the ambitious goal of reaching 70 percent access to electricity by 2030 and becoming fully carbon-neutral by 2050. It is already working to implement the National Electrification Rollout Plan for the country with support from development partners.

In the transport sector, improving transport infrastructure with sustainable and disaster-resilient qualities is a national-level priority, to which both the government and development partners are strongly committed. The sector has gone through comprehensive assessments such as expenditure and institutional reviews and has embarked on a comprehensive reform to enhance efficiency.

In the water and sanitation sector, transformative policies and regulation are ready to be approved. Two water utilities serving urban areas are, despite some inefficiencies, strong enough to potentially play an important role in further expanding water and sanitation coverage in peri-urban and rural areas.

In the ICT sector, the recent completion of the Coral Sea Cable may lead to further cost reductions. The completion of Kumul Domestic Submarine Cable and the introduction of low-cost handsets by mobile carriers will encourage increased uptake and spread the benefits of the Coral Sea Cable.

Papua New Guinea can improve its infrastructure situation by strengthening policy design, investment planning, and coordination among agencies and with development partners

It will also be important to introduce good sectoral and corporate governance and accountability, improve the operational and financial performance of the agencies in charge of infrastructure, and improve the balance between infrastructure investment and maintenance.

In addition, it will be increasingly important to find ways to involve the private sector in providing and maintaining the country’s infrastructure—for that, adequate regulation is a must.