Recent Economic Developments

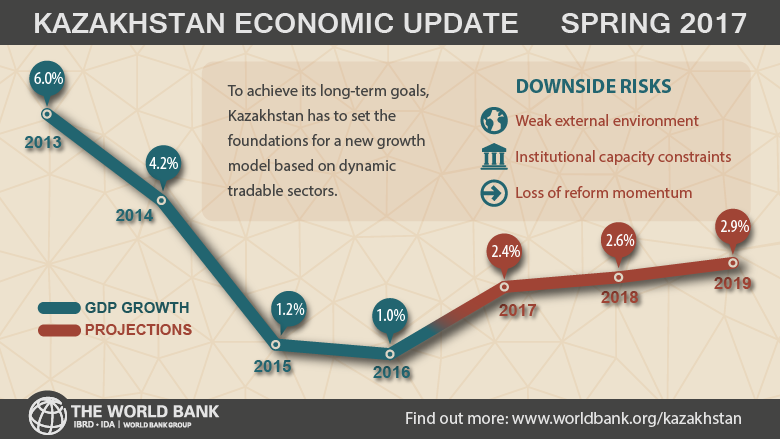

In 2016, Kazakhstan’s economy continued to suffer from a protracted slowdown in global oil prices and weak domestic demand. Real GDP growth declined from 1.2% in 2015 to 1% in 2016.

Lower oil prices and oil output widened the current account deficit. Investments in oil production, however, pushed up inflows of net foreign direct investment, more than offsetting the current account deficit. This enabled the Central Bank to partially replenish its international reserves, which it had drawn down to finance foreign exchange interventions in previous years.

Private consumption weakened considerably in 2016 due to the pass-through effect of currency devaluation, which pushed the inflation rate to an average of 14.6% for the year and undermined the purchasing power of households. Official data suggests that average real wages declined by 0.9%. As real incomes fell, the poverty rate (measured at the international poverty line of US$5 per day) rose to an estimated 19.8%.

Macroeconomic policy

During 2016, the government’s macroeconomic policy stance remained accommodative, seeking to stimulate domestic demand and the non-oil economy. As the economic slowdown continued, the authorities postponed fiscal consolidation and extended economic support measures, financed by the oil fund and additional borrowing. The economic support program is focused on fostering domestic demand through higher public wages and social transfers, continued provision of subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and small and medium-sized enterprises, and more recently, on extended support to the banking sector.

The Kazakh authorities are planning to address vulnerabilities in the banking sector by recapitalizing large banks, plagued with non-performing loans. The Central Bank also started easing gradually its contractionary monetary policy as inflationary pressures subsided in the fourth quarter of 2016, while banks’ lending to the private sector remained depressed.

Economic Outlook

In the medium term, Kazakhstan’s economic growth is projected to pick up slowly, but to remain much lower than before 2014 (when the oil price shock hit the economy). Real GDP rates will hover around 3% in 2017-19.

As oil prices are projected to recover gradually and off-shore oil from Kashagan to more than offset the observed declines in traditional oil output, export revenue will increase and impact positively on the current account and fiscal balances. Nevertheless, with the projected oil price level at a low of $55-60 per barrel, both balances will remain in deficit.

In the longer term, Kazakhstan’s desire for an economic transformation towards more sustainable and inclusive growth will require completing macroeconomic adjustment to fit the new normal, addressing the legacy of SOEs and other financial sector issues, and fostering the development of a more dynamic, export-oriented, and productive private sector.

Special Focus: Agriculture as a Potential Driver of Growth

The agriculture sector comprises an important piece of Kazakhstan’s push to diversify its economy and generate employment. President Nazarbayev named agriculture “a new driver of the economy” in his 2017 address to the nation - Modernization 3.0.

Indeed, Kazakhstan has tremendous potential to raise rural incomes, create jobs, and contribute to economic diversification by improving the competitiveness of its agriculture sector and adding additional value to output through processing. There are also significant opportunities to increase labor productivity in agriculture—which remains below that of Russia and Belarus—and to employ unutilized land, which represents almost 15 percent of the country’s total arable land.

Kazakhstan is well-located to serve the growing traditional markets in the region, as well as new markets in China, India and the Middle East. This, along with the scale of agricultural resources available, makes Kazakhstan a potentially attractive investment for domestic and foreign investors.

However, despite government support over the last ten years, the agro-food trade balance is negative. To become a real driver of growth, development of the agro-food industry (or processing agriculture), which is currently only about half size of the agricultural production, should pick up significantly. Taking into account the risk-prone nature of the sector, the primary way to raise agricultural output should be productivity growth based on research, innovation, dissemination, and adoption of new technologies and know-how.

Apart from this, the enabling environment for agro-business development remains an area of concern. Raising the attractiveness of the sector for investors should be an important policy priority, paying particular attention to investment-entry constraints (the provision of various licenses and permits), as well as investor-protection constraints (fair and equitable treatment of investor grievances).

In addition, agricultural productivity greatly depends on public investment in rural roads, utilities, and communications - as productivity declines significantly where travel time to markets exceeds four hours. Public-private partnerships should encourage private investment in storage, distributional infrastructure, and processing facilities.

As for financial resources, international experience demonstrates that a better access to finance for farmers can be achieved by developing commercial relationships between small farmers and the food industry that can provide significant finance to small farmers through structural financing.