Skills development is at the center of changes happening in education and labor markets amid the global mega trends, such as automation, action against climate change, the digitalization of products and services, and a shrinking labor force, which are changing the nature of work and skills demands. Consequently, skills and workforce development systems must proactively adapt to fast transformations posed by automation, climate action, digitalization, and the evolving labor markets.

These evolving trends will redefine the paradigms of education and workforce development systems globally. In the dynamic landscape of the modern global labor market, education and workforce development systems must become more personalized, accessible (allowing for remote and hybrid learning), and continuous along throughout workers’ careers– placing “skills development” at the heart of these global transitions. Moreover, skills systems globally (and notably in LMICs) will need to adapt to the fact that many workers will engage in freelancing/informal jobs or self-employment that need to become more profitable, productive, and conducive for economic growth.

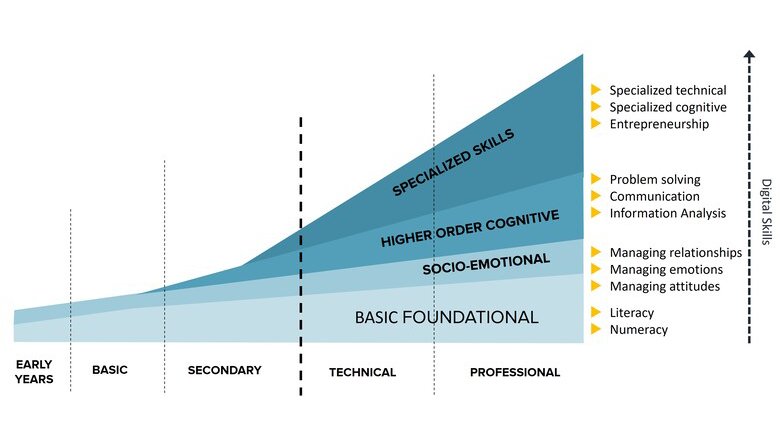

To succeed in the 21st century labor market, one needs a comprehensive skill set composed of:

- Foundational and higher order skills, which are cognitive skills that encompass the ability to understand complex ideas, adapt effectively to the environment, learn from experience, and reason. Foundational literacy and numeracy as well as problem-solving, communication and informational analysis are cognitive skills.

- Socio-emotional skills, which describe the ability to manage relationships, emotions, and attitudes. These skills include being able to navigate interpersonal and social situations effectively, as well as leadership, teamwork, self-control, and grit.

- Specialized skills, which refer to the acquired knowledge, expertise, and interactions needed to perform a specific task, including the mastery of required materials, tools, or technologies. Specialized technical and cognitive skills as well as entrepreneurship skills are included in this category.

- Digital skills, which are cross-cutting and draw on all of the above skills, describe the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate, and create information safely and appropriately.

Skills are a cornerstone for the green-digital transition. The development of skills can contribute to structural transformation and economic growth by enhancing employability and labor productivity and helping countries to become more competitive.

Yet, skills gaps are a main constraint, especially in LMICs, to achieve jobs rich economic growth for the digital and green transition. In this regard, most countries continue to struggle in delivering on the promise of skills development:

- There are huge gaps in basic literacy and numeracy of working-age populations, as 750 million people aged 15+ (or 18 percent of the global population) report being unable to read and write, with estimates being nearly twice as large if literacy is measured through direct assessments. Large-scale international assessments of adult skills generally point to skills mismatches as well as large variation in the returns to education across fields of study, institutions, and population groups.

- Megatrends such as automation, action against climate change, the digitalization of products and services, and a shrinking and aging labor force, will transform over 1.1 billion jobs in the next decade.

- About 450 million youth (7 out of 10) are economically disengaged, due to lack of adequate skills to succeed in the labor market.

- Over 2.1 billion adults need remedial education for basic literacy, numeracy, and socio-emotional skills.

- About 23 percent of firms cite workforce skills as a significant constraint to their operations. In some African and Latin American countries, this share rises to 40–60 percent.

- Most African and most South Asian countries do not have data on workforce skills.

- The global economy could gain an estimated US$6.5 trillion in the next seven years by closing workers' skills gaps, representing 5-6 percent of their GDP. Nonetheless, most countries invest less than 0.5 percent of the global gross domestic product in adult lifelong learning.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has brought the pre-crisis vision of equitable, relevant, and quality skills development into sharper relief, adding unforeseen urgency to the calls for reform and highlighting the huge costs of inaction. As a result of the pandemic, 220 million post-secondary students (est.) dropped out of school or lost training opportunities.

The key issues countries need to tackle for skills development are:

- Access and completion. Across the world, investments in education and skills development—from preschool through post-secondary education to vocational training—have high returns. The wage penalty for low literacy is nine percentage points in Colombia, Georgia and Ukraine, and 19 percentage points in Ghana. And the opposite is also true: in Brazil, graduates of vocational programs earn wages about 10 percent higher than those with a general secondary school education. Still, provision of equitable access is a challenge in many low-income and middle-income countries.

- Adaptability: The rapid pace of technological advancements and evolving labor markets can make technical and specialized skills quickly outdated. On the contrary, transversal skills, such as critical thinking, problem-solving, and adaptability, will become more transferable and resilient to changes in the job market. Evidence shows that post-secondary graduates who possess adequate occupation-specific technical skills but lack strong foundational and transversal skills, often face challenges in adapting to work-related changes.

- Quality. Many young people attend schools without acquiring basic literacy skills, leaving them unable to compete in the job market. More than 80 percent of the entire working age population in Ghana and more than 60 percent in Kenya cannot infer simple information from relatively easy texts. For those who access technical and vocational training at secondary and post-secondary levels, returns can vary substantially by specialization and institution. In particular, technical and vocational training (TVET) systems in many countries face challenges related to quality assurance, resulting in perceptions of the vocational track being a second-best option compared to general secondary or tertiary education.

- Relevance. Technical and vocational education and training —which can last anywhere from six months to three years— can give young people, especially women, the skills to compete for better paying jobs. Nevertheless, more needs to be done in terms of engaging local employers to ensure that the curriculum and delivery of these programs responds to labor market needs.

- Efficiency. Challenges related to governance, financing, and quality assurance also impact the efficiency of skills development programs. The resulting unnecessarily high costs can limit opportunities for disadvantaged youth and adults to access these programs. The good news is that the evidence on what works and what does not in skills development, and for whom, is growing. At the World Bank Group (WBG), we support governments around the world in collecting data and designing, implementing, and learning from reforms and programs aimed at addressing the most fundamental challenges of skills development.

To connect with our Skills community of 2100+ people interested in the field:

- Subscribe to the Skills4Dev Knowledge Digest, a newsletter that curates recent reports, papers, literature reviews, and blogs on the topic of skills and workforce development. Past issues are listed to the right under Resources.

- Sign up to receive event invitations to webinars on different Skills-related topics.

Last Updated: Apr 25, 2025