Vietnam’s rapid economic growth and its increasing energy demand have led to an exponential increase in GHG emissions, leaving the country with the second highest air pollution levels in Southeast Asia in 2019. To meet its development and climate change goals, the new domestic carbon emission trading scheme enabled by Vietnam’s revised Law on Environmental Protection aimed to create a carbon pricing instrument that will penalize emitters of GHG emissions based on the principle of “polluter pays.”

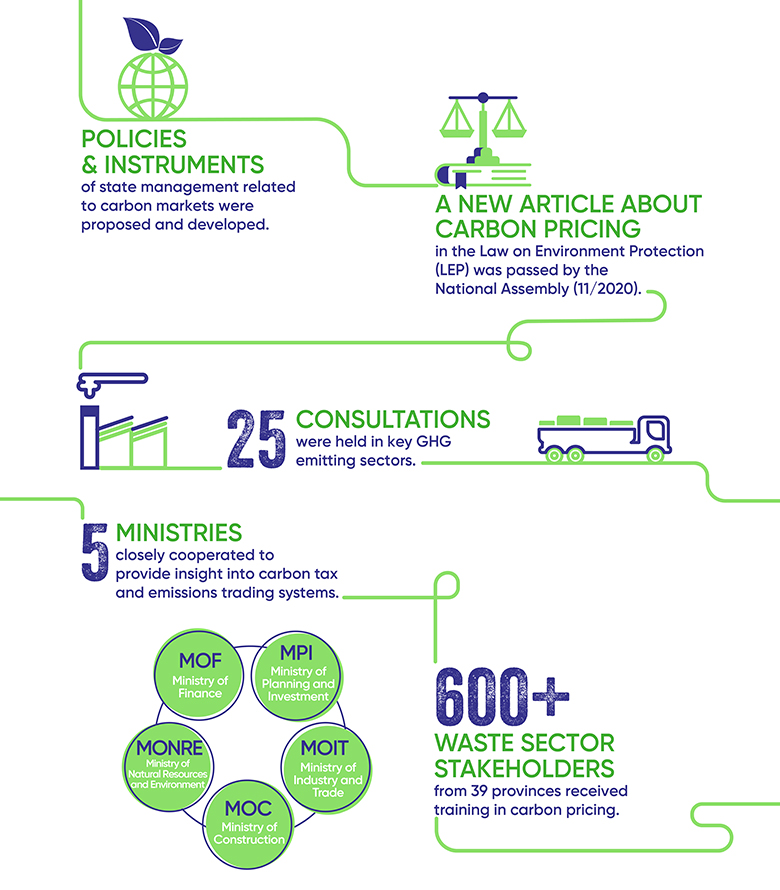

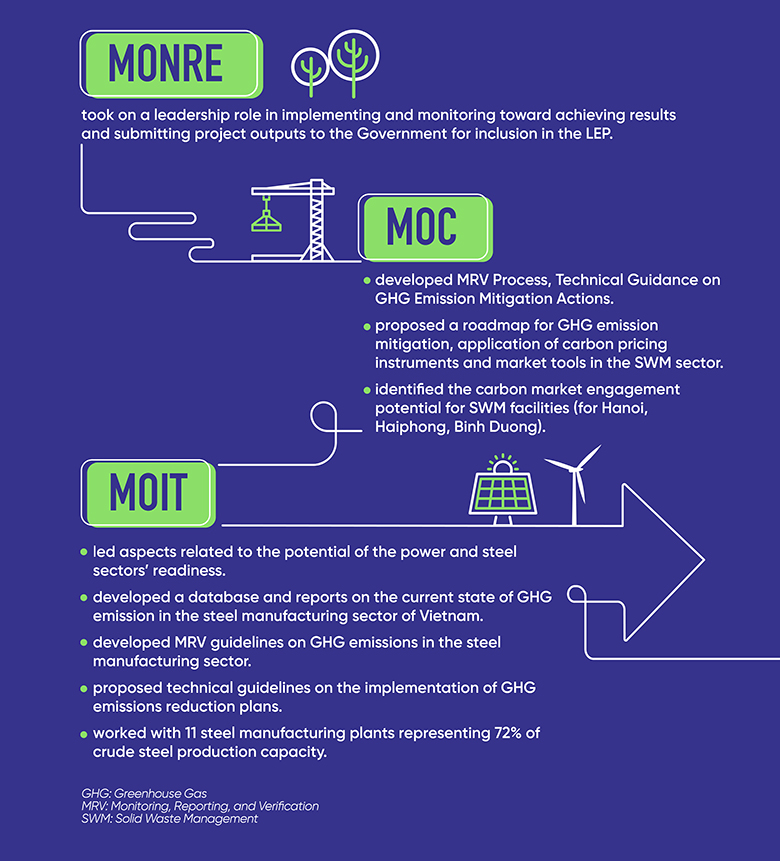

The carbon emission trading scheme (ETS) envisioned creating a market instrument through which production facilities, localities, and countries seeking to reduce their contribution of GHG emissions could buy credits to offset their actual GHG emissions. The carbon pricing mechanism would be supported by complementary policies and instruments such as the national GHG inventory system, monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) system, National Registry. In line with international best practices, the Vietnam ETS was expected to be applied to big emitters first before being scaled up to encompass smaller entities.

Free four green birds with one legal key

The new law addressed four major environmental and developmental challenges.

First, . Vietnam’s national carbon intensity per GDP increased 48 percent between 2000 and 2010, the second highest in East Asia. Between 2010 to 2020, the CO2 emissions nearly quadrupled, largely from coal-based power generation, industrial expansion, and a growing transport sector.

The rising air pollution levels amounted to over 60,000 deaths in 2017. Reducing emissions would therefore save thousands of lives in Vietnam.

Second, . Vietnam has been particularly vulnerable to climate change: extreme weather events have been occurring more frequently and rising sea levels threatened to flood important economic zones in the coastal areas, potentially forcing millions of Vietnamese to relocate.

Vietnam aimed to reduce nine percent of its GHG emissions compared to business as usual with domestic resources as envisioned in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and could potentially increase its reductions to 27 percent from business as usual with international financial support. At COP26 in Glassgow, Scotland, Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh announced that Vietnam aims to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050. The adoption of carbon pricing was expected to help deliver on these reductions while supporting the country as it tapped into its substantial renewable energy potential and transitioned to a low-carbon development model.

Third, . The trading mechanism was expected to create incentives for businesses to invest in solutions for GHG emission reductions and support achievement of the common goals.

Finally, , including to the European Union (EU) market.

Should Vietnam fall short of developing a domestic carbon market and fail to achieve decarbonization required to meet the EU requirements, then EU carbon standards could become a barrier for many Vietnamese exports to the European Union and many other markets. Besides, EU bilateral cooperation with other national carbon emission programs such as China’s could put Vietnamese exporters at a competitive disadvantage.