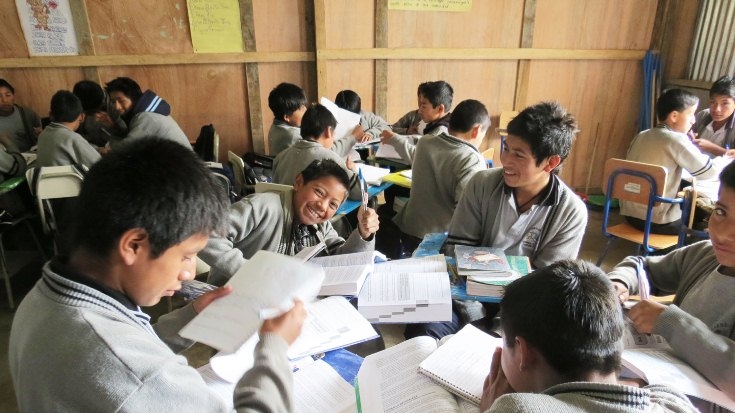

“They hit me, insult me, call me names,” says a high school student when describing a typical day at his school in Latin America. His is not an isolated case: beatings, insults and harassment form part of daily life for millions of Latin American children.

In fact, more than half of sixth-graders in the region report having been the victim of some type of violence at the hands of their classmates (theft, insults, beatings or threats), according to a study published in the magazine of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

In Mexico, nearly 69% of high school students who responded to an Education Ministry survey said they had experienced some type of aggression or violence at school. In Brazil, 70% of students reported having seen a classmate being intimidated at least once, according to Plan International. UNICEF reported that 66% of students in Argentina said they were aware of frequent harassment of students.

These figures clearly demonstrate that different types of violence are rife in Latin American schools. This situation is directly related to the environment, the communities and societies where those schools are located. According to Joan Serra Hoffman, a citizen security expert at the World Bank, “a school is not an island.”

“The most predictive factor is the level of violence in the surrounding area,” she said. How safe it is to travel to and from school is crucial, for example, as well as whether there are safe routes or adequate supervision in the area around the school.

“Generally, schools with higher levels of violence are located in less organized communities,” she added.

A violent continent, violent schools

According to experts, this classroom violence is a reflection of our experience in the region, the world’s most violent. Latin America has 10% of the world’s population but 30% of its homicides. Of the 50 cities with the highest murder rates, 42 are in Latin America.

But there is hope, according to Serra Hoffman. School is the ideal place to create a “refuge” where students can “develop co-existence skills.” After all, she said, young people sometimes spend more time with their teachers and classmates than with their parents.

Several initiatives have been implemented to promote peaceful co-existence and tolerance in schools. Medellin, for example, has the Mi Sangre Foundation of singer Juanes, which implements programs to improve school environments.

Sebastián Álvarez, a young participant from the Comuna 13 neighborhood known for its history of violence, said that the Mi Sangre project is about painting and writing, but also about “creating people with the capacity to forgive, to love, to engage in dialogue and to communicate.”

The role of the community

According to the World Bank expert, one of the first things to consider is the link between school and community.

“Frequently, the education sector is at the state or federal level and the link that should exist with the community near the schools is not there, even though it is an important ally,” Serra Hoffman said. She believes that schools and communities should work together to improve safety on the route to school, to have spaces for recreation and to create a healthier environment.

Additionally, it is important to encourage dialogue between schools and parents. “There were many initiatives in which schools consistently opened their doors to parents and the community as part of their pedagogy,” said Serra Hoffman. Several Latin American schools offer cultural activities or workshops for parents.

A healthy school environment can contribute to reducing violence as well as improve other factors, such as preventing teenage pregnancy or illicit drug consumption, according to the expert.