SUMMARY

The issue: traditional estimates

FAO estimates from 2011 suggest that as much as 37 percent of food produced in Sub-Saharan Africa is lost between production and consumption. Estimates for cereals are 20.5 percent. For post-harvest handling and storage loss only, the FAO estimate is 8 percent, and the African Post-harvest Losses Information System (APHLIS) estimate is 10-12 percent.

These high estimates have motivated international attention to PHL. Yet interventions typically focus on improving on-farm grain storage techniques for small-scale farmers. The estimates use extrapolation from purposively sampled (and often older) case studies that may focus on areas where PHL is largest. More and better quantification of (on-farm) grain loss is needed (which can then be compared with the costs of improved postharvest practices). Also needed is a better understanding of farmers’ behavior in adopting improved postharvest technologies.

The Analysis

The Living Standards Measurement Study–Integrated Surveys on Agriculture includes nationally representative household surveys from six countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. Farmers provided socioeconomic information about their households, agricultural production systems, and share of PHL for their crops. This paper uses these self-reported estimates to gauge the extent of PHL among maize producers and its agroecological and socioeconomic drivers in Malawi, Tanzania (two surveys), and Uganda. Although prone to measurement error, farmers’ self-reported estimates are drawn from nationally representative samples, thereby avoiding overestimation from sample selection bias. Harmonization across surveys facilitates cross-country comparison. And estimates likely reveal the losses that farmers deem important, which is critical when assessing likely adoption of improved postharvest storage techniques.

The Results

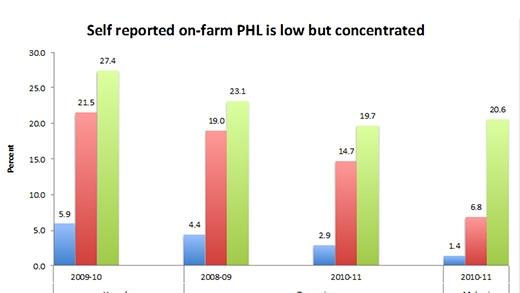

- Estimates national maize harvest loss are between 1.4 percent in Malawi and 5.9 percent in Uganda, which are substantially lower than the estimates of FAO and APHLIS.

- Only a minority of farmers reports a loss, with average losses ranging between 20 percent and 27 percent of the total maize harvest.

- Use of improved storage technologies is extremely low, between 0.6 percent in Uganda and 12 percent in Tanzania. Use of postharvest crop treatment, such as spraying or smoking, is higher, from 63 percent maize harvest in Uganda, where PHL is highest, to 10.8 percent in Malawi, where it is lowest.

More in-depth multivariate analysis of the Tanzania 2008 food crisis experience shows the following:

- Economic incentives substantially reduce PHL, widening the gap between pre- and post-harvest food prices in more remote markets.

- Climatic factors (particularly heat and humidity) substantially increase PHL.

- PHL is less for farmers with post-primary education.

- Household poverty does not appear to affect PHL.

- Female-headed households tend to experience lower PHL.

- PHLs were less likely to occur in households with the head having post primary education (not just completed primary).