The World Bank issued today the Tenth Economic Update for the Republic of Congo: Reforming Fossil Fuel Subsidies. Here are some highlights from the report:

1. Broad-based economic recovery, but risks loom

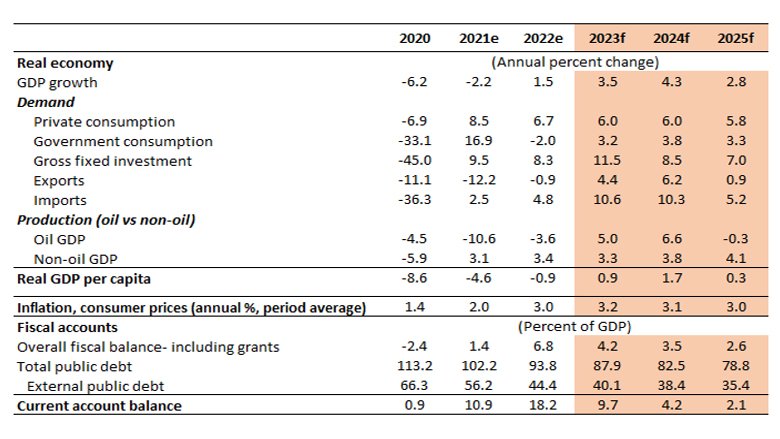

Following a growth rate of 1.5% in 2022, the Congolese economy is expected to continue to recover gradually from its recent protracted recession. The Republic of Congo (ROC) GDP is projected to grow at 3.5% in 2023 and to average 3.6% in 2024-25. Oil sector growth will be driven primarily by the resumption of investment by oil companies. Non-oil sector growth will be spurred by agriculture and services, and the implementation of structural reforms on the supply side; and by the continued clearance of government arrears, and the gradual increase in social spending and public investment on the demand side. However, there are several downside risks to the outlook including volatile oil prices and unsteady oil production, an escalation of the war in Ukraine and related spillovers, and a further tightening of global or regional financial conditions.

Key economic indicators of the Congolese economy

2. ROC’s fiscal health is mixed

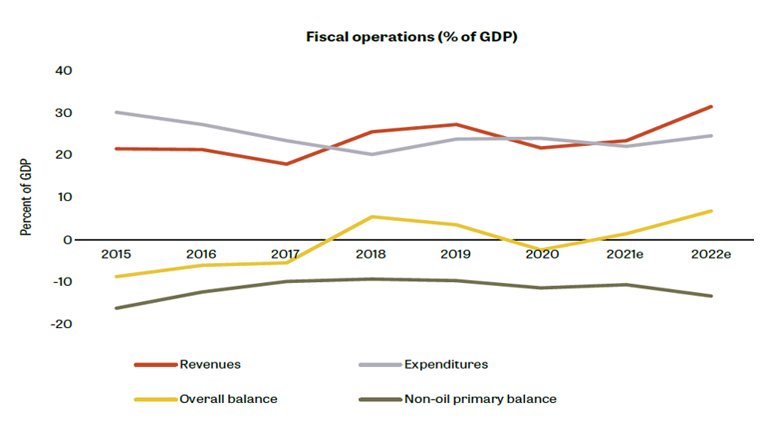

Although oil production declined in 2022, high oil prices led to a significant increase in government revenues, which together with a more moderate increase in government spending, resulted in a budget surplus of 6.8% of GDP. However, the non-oil primary balance deteriorated, mainly due to energy subsidies which increased from 1.3% of GDP in 2021 to 3.4% of GDP in 2022.

The overall fiscal surplus improved, but the non-oil primary deficit widened

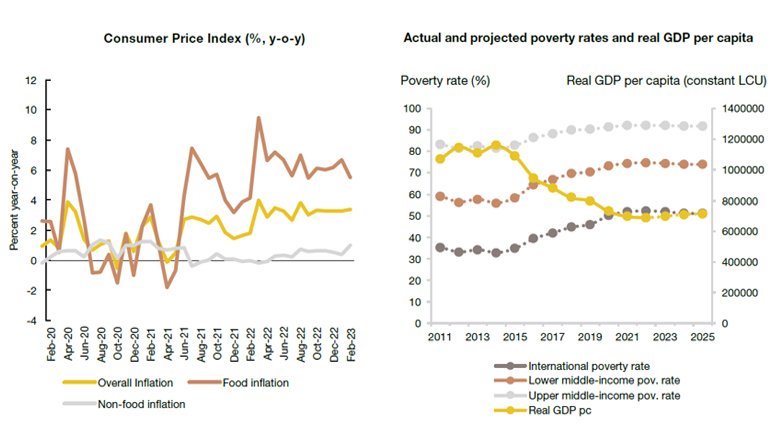

3. High food inflation is exacerbating food insecurity

Disruptions in global supply chains and high international food prices drove inflation in Congo, especially on food. Food prices increased by 6.2% in 2022 (y-o-y), pushing overall inflation to 3.0%. The increase in food prices is worsening food insecurity in a country where 56% of the population is already severely food insecure and where the poverty level is high. The poverty rate (using the international poverty line of $2.15 a day) reached 52.5% in 2022 from a low of 33% in 2014.

Food prices are increasing, exacerbating socio-economic challenges

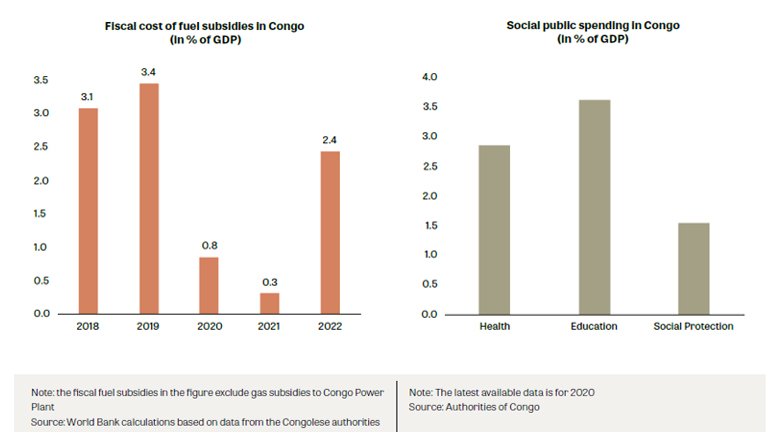

4. Fossil fuel subsidies are a significant fiscal burden

Oil subsidies increased sharply in 2022, reaching an estimated 2.4% of GDP – about four times what was planned in the initial budget law for the year – from an average of 0.6% of GDP in 2020-21. Due to the sharp increase in international oil prices last year, regulated domestic prices acted as a strong deterrent for imports of fuel by the private sector. This situation, coupled with the limited capacity of the national refinery, led to fuel shortages across the country. In response, the authorities decided to cover the losses incurred by importers of refined oil.

The use of public funds to freeze retail fuel prices diverts resources from alternative energy sources. Based on latest available data, expenditure on oil subsidies as a percentage of GDP is higher in Congo than spending on social protection and close to the total public spending on health. In addition, Congo also lacks fiscal space to improve and maintain its infrastructure, such as paved roads or reliable electricity: only 13% of the road network is paved, compared to 18% in Sub-Saharan Africa. Fuel subsidies also introduce environmental and market distortions, preventing efficient use of energy and the development of renewable sources of energy or the adoption of low emitting development solutions.

Public expenditure on oil subsidies in ROC increased sharply

5. Fuel subsidies benefit the wealthy

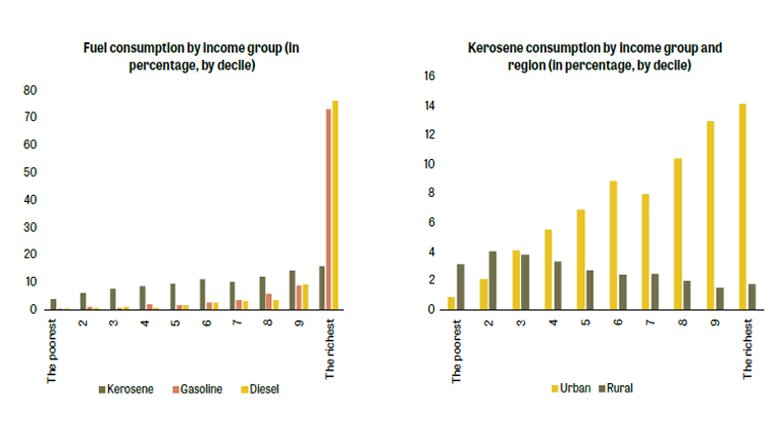

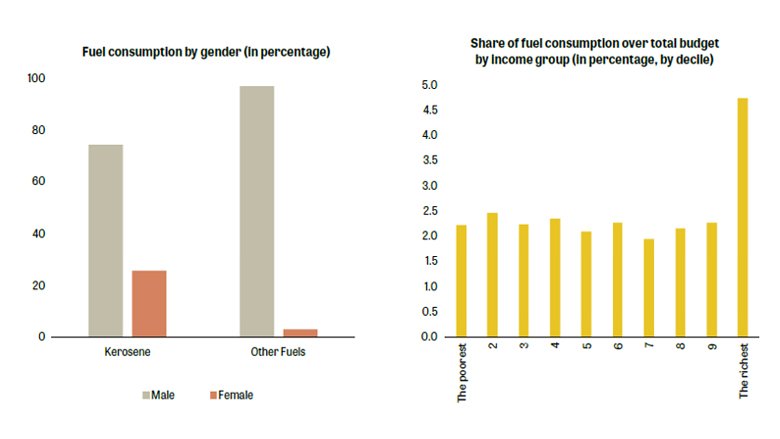

While fuel subsidies aim at supporting consumers’ purchasing power and, more particularly, that of the most vulnerable, these subsidies actually benefit the richest segments of the population, especially those living in urban areas. The richest decile of the population consumes 77% and 73% of diesel and gasoline, respectively, while the poorest consume less than one percent. By contrast, kerosene is much more equally distributed across income groups, although the richest still benefit more from subsidies on this fuel when compared to the poorest deciles.

Fuel subsidies are mostly captured by male-headed rich households living in urban areas

6. A pro-poor approach to fuel subsidy reform

International experience shows that removing fuel subsidies has been difficult. In many countries with limited social safety nets, a generalized subsidy is seen as a part of the social contract. This could be particularly true for oil-producing countries where fuel subsidies are sometimes perceived as a way for the general population to share directly in the country’s oil wealth. A number of general principles can be drawn from the experience of countries that have carried out fuel price adjustments:

- Prioritize the removal (or substantial reduction) of the subsidy that represent the highest fiscal cost and is consumed most by the richest

- adopt a price smoothing mechanism that offers a balance between excessive price volatility and fiscal risks;

- sequence the reform to allow households to adjust and the mitigation measures to be rolled out in a controlled fashion;

- engage in stakeholder consultations and carry out communication campaigns to address the concerns of various population groups.

Removing fuel subsidies – with the exception of kerosene - would result in a limited one-time increase in the price level. This would however impact the purchasing power of the population, as higher fuel prices would drive up prices of transport and other products and services. The report therefore recommends providing a strong mitigation package to protect the most vulnerable. This can be achieved by strengthening social safety nets, increasing social spending and transparency of public financial management, as well as supporting affected sectors such as transport.