Globalization has benefited an emerging “global middle class,” mainly people in places such as China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil, along with the world’s top 1 percent. But people at the very bottom of the income ladder, as well as the lower-middle class of rich countries, lost out.

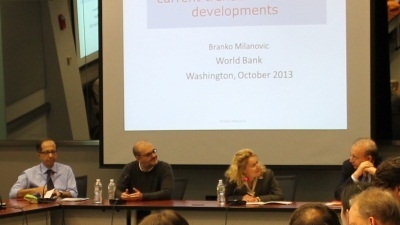

The findings, presented by economist Branko Milanovic to a packed audience of more than 120 people at a Policy Research Talk at the World Bank earlier this month, come just as the institution mobilizes around two goals: ending extreme poverty by 2030 and boosting the income growth of every country’s bottom 40 percent.

“Those goals are very ambitious, since the pace of growth is uncertain,” says World Bank Research Director Asli Demirguc-Kunt, who hosted the event. “Boosting shared prosperity also requires us to tackle inequality, not just within countries, but across countries as well, as globalization has made it easier for goods and people to move around the world.”

The new global middle class, about 400 million people, earned more and consumed more in the 20-year span before the global financial crisis hit in 2008, propelled by economic growth in countries such as India and China, said Milanovic, a lead economist in the Bank’s research department who has been studying inequality since the 1980s. He made the cross-country comparisons using a newly-created database of World Bank- managed household surveys that covers some 120 countries from 1988 to 2008.

The inflation-adjusted real income for the group around the global median rose 80 percent between 1988 and 2008. Their incomes, however, were still a paltry $3 to $5 per capita per day.

Not surprisingly, the top 1 percent of the world’s earners were big winners. Their real income went up by more than 60 percent during the 20-year period. In absolute terms, they saw their incomes increase by nearly $23,000 per capita per year, compared with some $400 for those around the median.

By contrast, incomes were almost stagnant among the world’s poorest 5 percent, despite the fact that real income did increase for the bottom and the second-lowest deciles.