Why is this tool necessary? And why now?

No matter what food prices are at the moment, food insecurity continues to be a challenge around the world, and its effects on the most vulnerable cannot be ignored. This tool adds to a robust global body of work to monitor food-related crises around the globe, and provides an integrative look at the issue, rather than just focusing on one aspect. We hope to add to the global knowledge on this critical issue and to continue to work with partners to better monitor food price crises as they unfold, deal with the consequences of crises, and ultimately help to prevent them from happening in the first place.

Now is the ideal time to launch this tool, given recent declines in global food prices and relative stability in domestic food prices. Instead of reacting to food price crises when they arise, and struggling to pull together the information needed to help countries cope, this tool takes a proactive approach to monitoring, so that in the event of a food price crisis, critical knowledge will be at the fingertips of relevant policymakers, citizens, and international bodies.

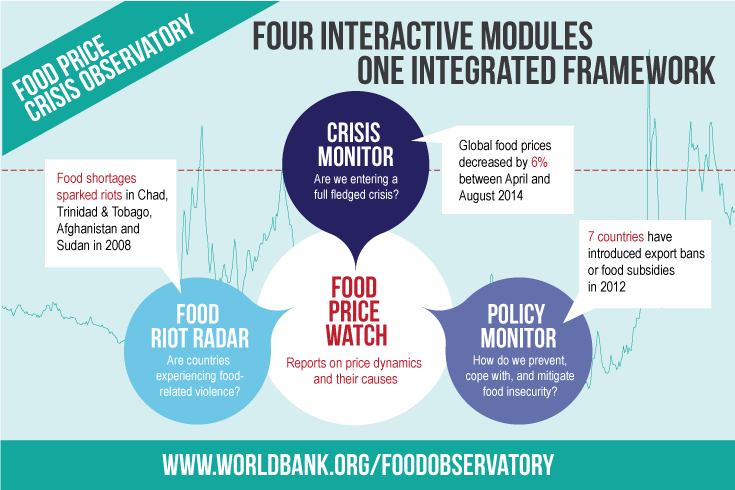

How do the four modules of the Food Price Crisis Observatory work together?

The Food Price Watch draws attention on the largest quarterly and annual food price variations and emphasizes the reasons behind those price movements. One key question emerges from the report: When do these large price fluctuations imply that we are entering full-fledged food price crises?

The Crisis Monitor specifically aims to answer the question posed by the Food Price Watch. Based on food price trends and macro-economic variables, it monitors countries' vulnerability to food price crises and their capacity to react to areas of concern. This module leads to two concrete questions: 1. How close are countries to a food price crisis? And 2. What means can countries use to prevent, mitigate and cope with the next one?

The Food Riot Radar tackles the first question and spots social unrest episodes related to food price instability. Two types of food riots are distinguished: Type 1 riots are mainly motivated by food inflation, while type 2 riots are mostly motivated by severe shortages.

The Policy Monitor addresses the second question; focusing on the policies used to prevent, mitigate and cope with food price hikes. The module is organized systematically according to 17 policy instruments that target specific actors. It tracks the implementation of and changes to policies worldwide that are relevant to food price crises.

The modules all feed into the Food Price Watch, and in turn work together to provide an integrated approach to crisis monitoring.

I’m not a technical expert- can I use this tool?

Absolutely! It is meant for everyone from very technical experts to university students to citizens in countries around the world who have an interest in the topic. Feel free to contact us if you are researching this topic—we’d be happy to hear your ideas.

I published a paper on this very topic. Could you feature it?

We are always open to learning more and featuring partners’ work in the Food Price Crisis Observatory. Send an email to any member of our team (see the right-hand column) and we’ll be happy to take a look and hear your ideas.

It looks like my country is entering a food price crisis, according to the Food Price Crisis Observatory—should I take this as an official declaration?

No. The Food Price Crisis Observatory will not and should not be used by the World Bank Group or its partners to declare global or national food crises. There are existing international venues and engagements for such declarations to be collectively made and this tool should never be used to justify unilateral declarations.

I’m a member of the media and writing a story on food-related violence—can I interview someone on the team?

Of course! Please contact our Communications Lead, Maura Leary, through the email address on the right-hand column of this page and she will be happy to work with you to get you what you need.

How often do you publish Food Price Watch?

As of the September 2014 issue, the report will be published twice a year, rather than quarterly. You can, however, keep up with food prices, policies, and riot episodes here in the Food Price Crisis Observatory, which will be updated in between issues of Food Price Watch.

I’ve seen similar tools out there—what is different about the Food Price Crisis Observatory?

There are indeed a number of very useful tools out there that focus on different aspects of food price crisis monitoring. The Food Price Crisis Observatory, rather than focusing on one piece of the puzzle, provides a holistic view of the issue and uses its four complementary components to create an integrated approach to crisis monitoring. It simultaneously tracks food prices, monitors crises at the global, national, and country level, keeps track of food-related violence when it occurs, and identifies policies that countries have or have not undertaken to mitigate, cope with, and/or prevent food price crises. Our aim with this tool is not to replace any existing tools, but rather to complement them and add to the global knowledge base on this issue.