Started in 2005 and closed in June 2013, SHEP’s objective was to help the Ministry of Higher Education progressively restore basic operational performance at a group of core universities in Afghanistan. SHEP began with a grant of US$40 million, and originally supported six universities (Kabul, Balkh, Herat, Kandahar, Nangarhar, and Kabul Polytechnic), mainly in physical infrastructure and improvement of staff development, curriculum and equipment. With additional funding in 2010, six more universities were added (Bamyan, Khost, Takhar, Jawzjan, Al-Beroni and Kabul Education University).

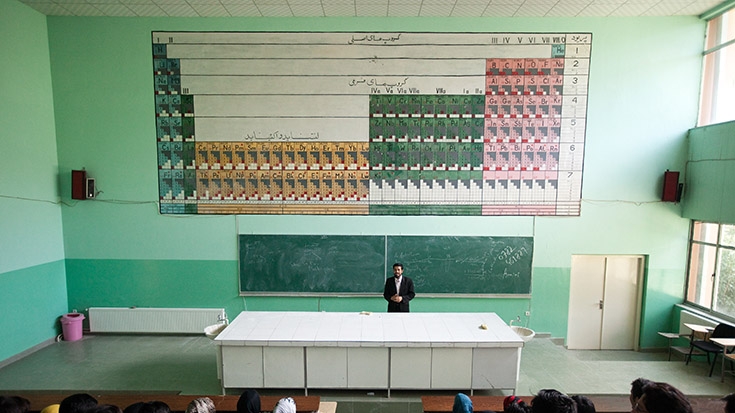

Civil engineer Hafiz Dost, from the SHEP office at Afghanistan’s Ministry of Education, was responsible for restoring the science faculty buildings at Kabul University. It was a daunting task, he recalls. “They were bombed out. Bricks were destroyed. The roof was missing in places. Not much was left really, but we were determined to rebuild it in the proper way,” says Dost, thumbing through an album of photos that shows some of the devastation and subsequent reconstruction.

A faculty of excellent quality

In 1968, German architects designed the main faculty building that houses chemistry classrooms and laboratories, says Dost. Classes for physics, biology and mathematics take place in another nearby building that was not as badly damaged.

Dost especially appreciated the modern, clean lines of the devastated chemistry building. “It was a good, solid building that deserved to be saved and we tried our best,” he says.

SHEP provided $1 million in funding for the work in 2009, and Dost managed to complete it under budget for about $861,500, he says. “Still, we made sure to use good quality materials, like marble and granite for the floors, aluminum-frame windows and such. This place and the students deserve it.”

Today, about 1,500 students are studying science in the two faculty buildings. They represent a fraction of the 20,000 young people who applied last year, says the dean, Taniwal.

“Of course, if we had more space, we could recruit double or even triple the number of students. Our country needs these people. I’m telling my students all the time, and people in government also, if you want to make a good country, please support science.”

In the newly refurbished faculty buildings, students are acquiring skills to work as engineers, teachers, in manufacturing, banks, government offices, industry, factories and NGOs, says Taniwal.

“Because of science, we have mobile phones and medicines. Science makes our lives possible, even easier. And we can pursue these goals because we have the classrooms and buildings to teach in. I put all my effort into making this faculty of excellent quality, like any developed country, because science is everything.”

SHEP support has provided laboratory equipment, chemicals, and other supplies for science experiments, although Taniwal says these materials are difficult to get and are frequently in short supply.

He says science was the third area of study, after medicine and law, established at the university more than 80 years ago. The university first opened its doors to students in 1932 during the reign of Mohammed Nadir Shah. Only after civil war halted classes, faculty and students fled. When the Taliban took over in 1996, a few male students were allowed to return, says Taniwal.

“I remember the fourth year chemistry class had just one student, the others had only three, and of course, girls weren’t permitted then.”

Partnership with foreign universities

Today, about 40 percent of the science faculty are women. Among the most recent graduates is 21-year-old Fatima Siddiqi, who majored in mathematics. Diploma in hand, she had returned during a break in her new job teaching at a prestigious local girls’ high school to get Taniwal’s signature on the document.

“It has all been very interesting for me. I love being a teacher. That is why I selected science for my studies,” Siddiqi quietly enthuses. Her family has always supported her education, she adds. Her mother is a teacher, and her father works in government. She has a brother in computer science, another in psychiatry, and a sister in the United States.

Siddiqi was recently awarded a scholarship to complete her Master’s degree in Egypt, she adds. “My family thinks education is very important and they want us all to do well.”

Another recent graduate, Rajab Akbari, 25, recently landed an important job in the government’s Ministry of Interior Affairs, helping to launch a new electronic system for national identification cards.

His parents are illiterate farmers in Bamiyan province in central Afghanistan. “My parents are very happy that I managed to finish my education,” says Akbari. “For them, it was impossible. And I think if I didn’t manage to study at this faculty, I could also do very little.”

Taniwal is keen to provide more opportunities for students, but a partnership with another foreign university is desperately needed, he says.

Another element of SHEP provided funding for university partnership programs, which offers support for curriculum development and revision, visiting professorships in Afghanistan and at foreign institutions, joint research and publication, and support for developing libraries, laboratories and other facilities.

Kabul’s science faculty recently completed a partnership with Delhi University in India, which trained professors in more modern teaching methods, offered scholarships and provided countless other benefits, says Taniwal.

“This is very important to have a relationship with another university, to be exposed to other ideas and methods. This is our number one priority now to find another wonderful partnership, so we can keep inspiring our students and faculty. We want to demonstrate all that science can offer here.”

Forward looking:

The World Bank team is working closely with the Ministry of Higher Education and the universities on preparing the next phase of support for higher education. A preparation grant of US$4.9 million was approved by the ARTF Management Committee in June 2013. Meanwhile the World Bank recently released a report, ‘Higher Education in Afghanistan: An Emerging Mountainscape’. This is the first time that the Bank has undertaken an in-depth study of the higher education sector in Afghanistan, which provides a wide-ranging and evidenced-based review. It surveys a variety of higher education systems, policies and reforms from the modern world particularly in areas where Afghanistan faces the greatest higher education policy challenges. It also provides a menu of policy options for policy makers in Afghanistan’s higher education system. The report is available on:

https://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/08/18197239/higher-education-afghanistan-higher-education-afghanistan-emerging-mountainscape